THE EXHIBITION

•

THE EXHIBITION •

‘Fragmented’

Chloe Kultgen graduated from Minnesota State University, Mankato with a BFA in Creative Writing. When she’s not reminiscing on the past or speculating about the future, she enjoys spending time by Lake Michigan looking for hidden treasures that wash ashore.

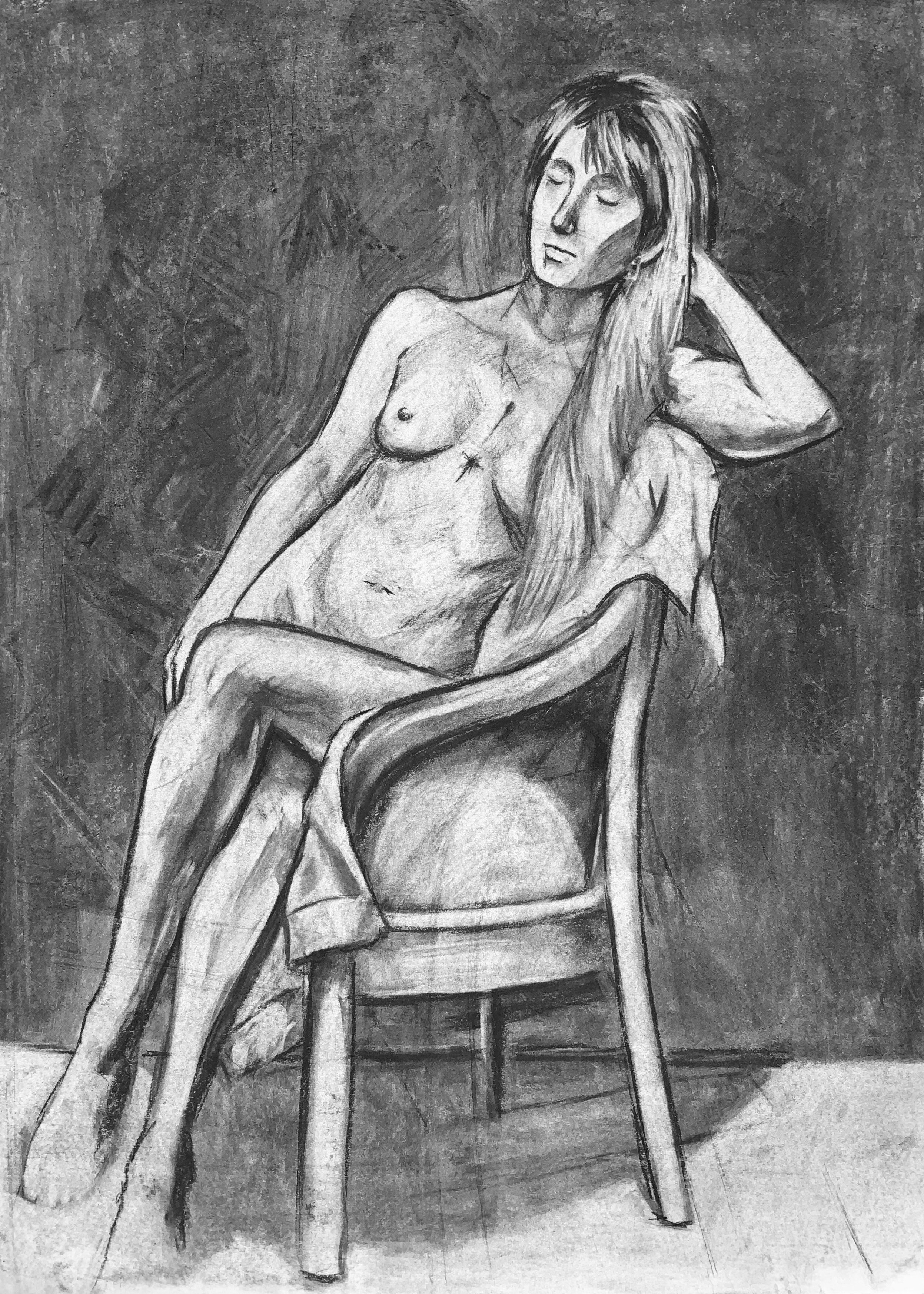

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldlpatten.newgrounds.com/art

Fragmented

I think there was a fear of self

that had found a home

within my bones

as a child, I had been left with

discarded pieces of safety

& forced to imagine what

unconditional love felt like

stranded

& made to scratch away

at my skin—

a desperate attempt to

understand why I deserved neglect

& question what was wrong with me

thought that if I searched within

& dissected myself enough

I would uncover what needed to be changed

yet the more I looked, the more I started to hate, the more I started to compare, the more I started to question, the more parts of myself became

s h a t t e r e d

by

m y

o wn

h an ds

until

I had

been

left

with

nothing—

my

identity

fragmented

but as I have been attempting to

figure out who I am now

&

constructing my foundation of needs

I have discovered that

home is a hug of self love

that will never let you go

&

home is about finding

the pieces of yourself

that you abandoned long ago

&

finally allowing them

a safe space to live within your bones

Chloe Kultgen graduated from Minnesota State University, Mankato with a BFA in Creative Writing. When she’s not reminiscing on the past or speculating about the future, she enjoys spending time by Lake Michigan looking for hidden treasures that wash ashore.

‘Tender’

Jovi Aviles is a teen writer whose work has appeared in The Malu Zine, PWN Teen, and Pen&Quill. Her favorite authors are Madelaine Lucas and Sylvia Plath. She is often found at her favorite cafe writing.

David Summerfield’s photo art has appeared in numerous literary magazines/journals/and reviews. He’s also been editor, columnist, and contributor to various publications within his home state of West Virginia. He is a graduate of Frostburg State University, Maryland, and a veteran of the Iraq war. View his work at davidsummerfieldcreates.com

Tender

The first time I saw my father cry was at confession. While I didn’t know what it was then, I remember sliding between the pews in my puffer coat, pretending I was a goat sliding down hills of marshmallow. I remember tracing the art sculptures in the Vatican with my index finger, pretending the crying angels were princesses welcoming me home.

When his divorce from my mother was fresh he fell out of that faith he used to preach to me before bed, mumbling quiet prayers into the shy tunnels of my ears. On those quiet nights–when snow was busy swirling and sticking slick to the windows of our empty house, the one being rescinded and collected back from the bank–he would tuck me in up to my chin. I would never tell him he was doing it wrong, even though the whiskey-stained sheets would scratch against my flesh like a pinecone and the chill from my window panes would reach the tips of my toes. Sending a shudder I’ve only ever felt on those lonesome nights, when I could almost feel my fathers faith slipping like cloudy bath water.

Sometimes, as he pulled me from the tub and wiped my hair and my face dry with damp towels, I saw faces in the water. Little clouds of ghosts swirling into the drain, whispering something indescribable. A secret swapped between bubbles. Later, I would believe that image to be the white holiness of my fathers religion sinking into the drain, leaking back into the ocean where hopelessness was a common ancestor in a sea of dreams left dead and bone-dry.

In the mornings with my father, I always woke up to the smell of pancakes. There would be batter smeared on the countertops and orange juice propped on the table ready for me to pour. I would pick out the splinters in my highchair that stuck my bare toes, while waiting for the pancakes to flip on my plate because while we couldn’t afford socks that winter, we could always afford batter and blueberries.

As if we weren’t getting pummeled to death with the weight of the world already crumbling on our tattered shoulders, this condemned God sends sickness to my fathers younger offspring.

My socks had all gone to my baby brother who was still at my mothers, getting nursed back to health after pneumonia ravaged him like starved, barbarian racoons. My mother attainted to him like a personal nurse, and sometimes I watched her nursing a few times that winter when my dad would drop me at her doorstep and wheel away in his cherry red convertible.

She would bundle up every inch of his skin in socks, these big, fluffy socks that were stained with my scraps of food and blood from my routine splinters. Then, she would take the big lard of fat that was my brother into her chest, warm him like he had been sitting out in the North for days while the wind whips his cheeks raw and red. I asked her to do that to me, once. To feel a touch other than my fathers calloused, construction hands. To feel the essence of my baby brother’s lotioned tummy, his lotioned face and feet. Maybe even to hear my mother’s heartbeat, hear Jesus whispering and confessing his identity to me. Maybe that would’ve made me reserve my Sunday mornings when I became a young, red-heeled woman.

“Can’t you be like that with me, mama?” I pleaded. She looked up from his face then, let him continue suckling what was left of her inside her aged, wrinkled breasts. “He needs tender.” She whistled through clenched teeth. Grizzly. “You had that tender before. You don’t need more.” She said, plainly. She looked through me like I was a hologram, like I was an aloof daughter mistakenly placed in the wrong house. A mute daughter who expresses feelings through her fingers, her wrists, her eyes.

And I did when my father buckled me in on Sundays. For months on end, those chilled, frigid months, we survived solely on the circle bread they would feed us between hymns. He

would get to drink the juice that smelled like roses and coins. I wasn’t old enough, or maybe I wasn’t holy enough. I never heard the priest right. I don’t think I ever heard him right until his old battered hands went up my skirt after my first confession, and he dangled his twisted fingers into a crevice I was told was too valuable to let another man destroy. But he justified it with the word of God, forgave me of all of my sins that had been littering my mind.

I walked out of that thin box fixing my skirt and wiping the blood from between my legs. My father was waiting for me by the great big doors, shook hands with the priest, an evil grin plastered on that wrinkly face, and led me to his car that was blanketed in iced snow. “Daddy?” I croaked on the way home.

“Yes?” he muffled through his mustache.

“Do God’s people commit sins?”

“Sometimes.” His eyes were locked on the road. We drove over frosted roadkill. “Are they forgiven?”

“They aren’t witnessed.” He cleared his throat. “They are pursued in silence.” I didn’t know what that meant as we traveled through dirt roads on flat tires. I merely felt the bump and potholes in the road a little stronger that night, I merely hurt a little more in the shower and on the toilet and under my sheets that still smelled of whiskey. I burned.

Jovi Aviles is a teen writer whose work has appeared in The Malu Zine, PWN Teen, and Pen&Quill. Her favorite authors are Madelaine Lucas and Sylvia Plath. She is often found at her favorite cafe writing.

‘Nothinginsomuch’ & ‘Like Chicken Pox or Poison Oak’

Justin M. Bushey is a poet who settled in the DC Metro area after enjoying the adventures and misfortunes from one coast to the other.

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldlpatten.newgrounds.com/art

Nothinginsomuch

My skin into sleet,

My shivers into sacrilege—

the black ice cuts me

cross-sectioned, leaves

the seconds trembling,

paints me with erudite

wisdom: I sink myself into the

pavement—I wash it away

with whiskey.

My emptiness into air,

My breath into transition—

dreams, then Capitol Hill at

dawn, city bus broken down

on the roundabout—I found

a t-shirt in the snowbank,

once worn by a mystic

who got tired, so

he grew up

and became hard.

Your star sign

into my viewless evening,

My shadow

into your paper-mache winter

when we sat lieless, hands

folded into simile like

paper cups and burnt coffee—

you, the silence of my morning,

and I, pollyanna-inert,

sharing a last stand between

tomorrow and

careless

innuendo.

Like chicken pox or poison oak.

My birds find the dark

imposing—it’s not properly

abstract. You know how it is

when we feel excessively real—

or entirely present. They sing

strange polygons, into and

out like pretense

woven through a plunging sky,

dislocated parallaxis, cold and

somewhat unlike storm gods.

This is how I kill my time in

our suburb persistent

cul-de-sac:

I think about how I remember

you were going to steal a Camaro,

a convertible, transmogrified green,

we’d name her something like

Shameless Reality and

she’d hold 115mph through Middle America

'til we hit the Rockies where the

plunging sky becomes dry land.

They say it’s different when you die out west.

But

my birds will never drown, they

only shudder—they become the

last moment to survive my windowsill

the last moment

into frantic

dawn,

muted,

itinerant,

utterly enthralled by unburdened

second chance.

Justin M. Bushey is a poet who settled in the DC Metro area after enjoying the adventures and misfortunes from one coast to the other.

‘The White Pony’ Contest Winner

Kelsey Stewart’s work often engages with fractured systems and the emotional cost of survival within them. She is currently pursuing a Master’s in Creative Writing at Harvard. Originally trained as an opera singer, she performs with the Houston Grand Opera and hold a BA in music from Loyola Marymount University. Her fiction blends dark humor, social critique, and elements of absurdism, drawing inspiration from writers like George Saunders and Nikolai Gogol.

Lizzie Falvey is a Boston-based artist and educator who works in photography, monoprints, ceramics, and video. Her photographs here--digitized prints of 35 mm black and white film--are a quiet exploration of mood and atmosphere found in moments of human intervention in natural landscapes. She holds an MFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and her works have been shown regionally and nationally.

The White Pony

Winner of the Spring Short Fiction Contest 2025

It takes hours of practice to perfect the art of turning an ordinary white pony into a unicorn for children’s birthday parties. Meanwhile, my family packed their lives into duffel bags and walked through jungles, floated on leaky rafts, hitchhiked, and clung to the backs of rusted pickup trucks.

I have a cousin who lives there legally. He teaches paleontology at a community college—an essential worker, apparently. He told me that if I could do something spectacular, I might qualify for a visa based on talent. Talent alone, he said, could grease the wheels of immigration. He said this while microwaving a burrito and grading papers.

So, I bought a small white pony from the next town over. The owner warned me it was mean as hell. He wasn’t wrong. I fed it carrots and apples, brushed its coarse little coat, called it sweet names. But no. This pony was furious. It bit me constantly, like it had a personal vendetta. Which is probably why I didn’t feel too guilty when I started dyeing its fur pastel colors and strapping a plastic horn to its head.

My mother sold the house when she left. She kissed me on the cheek and wished me well. It broke her heart that I didn’t go with them. But I had my reasons. I didn’t want to seek refuge—I wanted a talent visa. I wanted to follow the rules, every last one, no matter how arbitrary or impossible.

I was ready for the hoops:

• National Anthem

Sung both straight and to the tune of Yankee Doodle Dandy

• Pledge of Allegiance

Recited forwards and backwards, without blinking

• The Amendments

All of them, in order, annotated, and dramatized if requested

• The Bill of Rights

Cross-stitched into a decorative throw pillow

I was determined to be impressive on paper. Talented. Deserving. Legal.

I lived in the pony’s stall to save money. The floor was hay and regret. I kept my paperwork in a waterproof bag and taught myself mindfulness from library books wrapped in plastic. I used the public bathroom at the feed store, where the clerk would say things like, “Still chasing that dream? Heh heh,” and I’d nod, as if it wasn’t crumbling in my hands.

Gym prep was non-negotiable. So was a full-body wax and a thick coat of glistening oil. I spent my last few dollars on rocky road protein powder. My town didn’t have a gym, so I had to improvise. I lifted water troughs. Curled sheep. Squatted hay bales until my legs gave out. The pony watched me with deep suspicion, like I was the lunatic in this situation.

At night, I showed him pictures of faraway places—big cities with glass towers, houses with more bathrooms than people, cars that looked like spaceships. Shopping malls the size of stadiums. I even showed him barns with air conditioning and tile floors. Livestock luxury. He tried to bite my head.

The other animals kept their distance, mostly. The goats were busy with their schemes. The rooster crowed in Latin some mornings, which I suspected was meant to mock me.

I read Dante, Locke, Foucault. Derrida, Heidegger, Plato. I practiced speaking with confidence, learned to enunciate while jumping rope, drank tea with honey to smooth my throat. I rehearsed answers to questions no one would ask.

“What is your greatest weakness?”

“Overthinking my own capacity for moral compromise.”

“What is the meaning of freedom?”

“It’s a stage. And everyone is auditioning.”

Finally, the talent round. This is where the pony came in.

I ordered about a hundred dollars’ worth of Swarovski crystals from a woman named Aisha. She included a free glitter pen and a note that said, Go get 'em, unicorn queen. I glued the crystals, one by one, onto a fake unicorn horn I’d painted myself. It shimmered like nonsense.

I trained that asshole pony to stop whipping its head around when it wore the horn. Mostly. Sometimes it would just stand perfectly still, eyes narrowed, and then—suddenly—slam its head into the barn wall.

Dyeing the fur was easier. It was basically just giving the pony a bath, which he pretended not to like, but I caught him leaning into the cold hose and the hairbrush. I don’t know if ponies are colorblind, but luckily there’s no mirror in the barn—because if he saw himself, it might’ve pissed him off even more.

Maybe the other barnyard animals had opinions. Maybe they whispered judgments about the pastel rainbow hair. Maybe the rooster was a traditionalist. Maybe the goats admired the boldness.

The day of the showcase arrived.

They set up a temporary stage in the civic center parking lot, between the expired food truck and a bounce house full of mildly sobbing toddlers. Contestants milled about in sequins and Spanx and modest heels. A woman dressed as the Statue of Liberty was applying last-minute bronzer. Someone else had brought a falcon. A man claimed he could yodel the Constitution.

I waited for my number. The pony tried to bite a small child who got too close. A volunteer offered me a pamphlet titled Pathways to Legal Citizenship: A Family Guide.

When my number was called, I walked onstage in my prom tuxedo, dragging the pony behind me. The horn was straight. The fur was gleaming, sherbet-toned. Aisha’s crystals caught the light like disco ball dreams. I did a little bow. The pony bit my ass.

“My name is—” I said. Then stopped. Because the judges—three government agents in matching polos and Oakley sunglasses—weren’t looking at me. One was eating a corn dog. One was texting. One was asleep.

Still, I did the routine. I made the pony do its pirouette. It did not pirouette. It sort of trotted in a circle, then defecated. The horn slipped sideways. The children in the audience screamed in delight.

I segued into my monologue: a dramatic reinterpretation of the First Amendment set to a medley of Sondheim showtunes. The pony tried to bolt.

When it was over, I stood there, panting, sparkling, waiting.

The judges didn’t clap. No one clapped.

They conferred, mumbling into clipboards. One finally looked up and said, “Thank you. We’ll let you know.”

Which is what they always say. Whether they will or not. Whether they already have.

Back at the barn, I fed the pony a bruised apple. He didn’t bite me that time. Maybe he was tired. Maybe he was resigned. Maybe, like me, he had started to understand.

I cross-stitched “Due to high volume, your application is still under review” onto a pillow that night. Just for practice.

Outside, the goats slept curled like question marks. The rooster muttered something judgmental in his sleep. The pony stood in the moonlight, glitter fading, horn askew, like he was waiting for something—anything—to change.

Kelsey Stewart’s work often engages with fractured systems and the emotional cost of survival within them. Like much of her fiction, "The White Pony" is interested in the contradictions of being—how ambition and delusion, hope and disillusionment, legality and legitimacy bleed together when the rules are designed to be out of reach. She is currently pursuing a Master’s in Creative Writing at Harvard. Originally trained as an opera singer, she performs with the Houston Grand Opera and hold a BA in music from Loyola Marymount University. Her fiction blends dark humor, social critique, and elements of absurdism, drawing inspiration from writers like George Saunders and Nikolai Gogol.

Author Kelsey Stewart

Interview with Kelsey:

Why are you a 'Breakout Creative'?

After earning my degree in music, I spent many years pursuing a career in opera, while secretly nurturing my love for writing on the side. Two years ago, I decided to take that passion seriously and enrolled in Harvard's Master's program in Creative Writing. Since then, I have grown tremendously as a writer and have begun submitting a few stories I’m proud of to literary journals, encouraged by my professors. Until now, my work has lived in academic settings, so I’m excited to share it more publicly and begin this next chapter.

What made you want to be a writer? Did you have any muses or guides along your way?

Writing is the one thing I can do from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. without ever getting tired. I think I’ve always known it was part of me. In second grade, during a make-your-own-picture book assignment, my teacher—Mrs. Clay—handed out little pre-stapled booklets for us to write in. After I approached her desk, asking for my fifth “extra booklet,” she smiled and said I was going to be an author someday.

I think she cut me off at ten booklets, so sadly, we will never know what became of the goldfish with the world's longest pearl necklace.

That early love for storytelling stayed with me, even as I pursued a career in opera. Today, I’m studying creative writing at Harvard, where I’ve been fortunate to work with incredible mentors like Ian Shank and Thomas Wisniewski, who have both played a significant role in the growth and refinement of my craft.

How would you describe your unique style and what do you think influences it?

My writing style blends dark humor, emotional depth, and surreal absurdity, often drawing on satirical frameworks to explore the breakdown of social systems, identity, and power. Influenced by writers like George Saunders and Kurt Vonnegut, I gravitate toward fractured realities where the bizarre coexists with the painfully human. Whether through speculative dystopias, emotionally fraught romantic comedies, or corporate absurdist tales, my work aims to unsettle, amuse, and provoke reflection.

If you had any advice for writers just getting started, what would you say?

Keep writing! Your first story might suck. So might your first draft. Big deal. That’s part of it. If you enjoy the process and keep showing up, you’ll get better. Every sentence, every rewrite, every false start is progress. The only real mistake is stopping.

Where can we find more of your work?

So far, most of my work lives in the inboxes of my professors, but I recently published my first story withThe Raven’s Perch. I’m excited to keep submitting and expanding my presence in the literary world.

Is there anything else you wish to tell us?

I’m committed to the craft and always seeking ways to improve. Thank you for the opportunity to share my work.

‘A Eulogy for Rincon’ Contest Finalist

Jill Bronfman was one of 12 Aspiring Novelists Selected for the Irish Writers Centre Novel Fair 2025, was the Barnes & Noble, National Essay Contest Grand Prize Winner, placed second in the Joan Ramseyer Memorial Poetry Contest, was named a semi-finalist for both the James Applewhite Poetry Prize and The Waking’s Flash Prose Prize, and received an honorable mention in the Storm Cellar Force Majeure Flash Contest. Her work has been accepted for publication in five collections and over thirty literary journals. She has performed in The Bay Area Book Festival, Poets in the Parks, The Basement Series, Page Street, Washington Square Annual Livestream, and LitQuake, and had her story about a middle-aged robot produced as a podcast by Ripples in Space. She has been accepted to residencies and conferences including Looking Glass, WonderMountain, and LitCamp.

Elizabeth Agre ran away from city life and now hides in the north woods of Minnesota along side the bear, wolves, and bobcats. She dabbles in writing, painting, and taking pictures. If not, she is probably out fishing.

A Eulogy for Rincon

Runner-Up for the Spring Short Fiction Contest 2025

Martina

It was obvious that she had drowned the dog. And that she had loved him, and cared for him nearly up until that point. Or maybe through that moment.

I found the dog in the toilet or next to it. His fur was white and curly and matted close to his small body. He looked like had just had a bath and was snoozing a bit. My training to clean the airport restrooms in no way included what to do with dead animals, and it took me quite a bit of time to notice, realize, and accept that this dog was dead.

I opened the envelope on the floor next to the dog. Rincon’s papers said he was healthy. His tags with his name and her name on it. Her address in the hills, up above La Jolla. Where you couldn’t even see or hear if your neighbor had a dog.

I called airport security, and they came, and then the police came and they took everything away except the puddle on the floor next to the commode. That part I knew how to clean up.

Sergeant Stefan Lubovich

Man, I hate pickup. Ninety percent of the time, it’s a gunshot wound and the blood is everywhere. Somehow, this was worse. The dog looked a lot like Snowball, my dog growing up. Snowball lived until he was seventeen, and went out with a steak and a pet, not like this.

I bagged the animal and the K-9 tags and the paperwork tucked neatly into an envelope beside him. The bags were blue but clear, and so nobody did this but I closed the dog’s eyes so he stopped accusing me. I had nothing to do with his death, but somehow I felt responsible. Like I could have gotten here a little earlier.

The call that brought me to the airport wasn’t about the dog, not originally. The first call was from the airport gate, where a woman was making a commotion because she couldn’t bring her dog on the flight to Honduras, or Guatemala, or maybe it was Panama. She had to get on the flight, she only had thirty minutes, the gate agent said when she called me. The woman was screaming at the gate agent, you could hear it in the background.

Tanya Mertens

I have seen a lot of whining, and a little anger. People are late, they are tired, and they all take it out on the gate agent. We’re not the highest-ranked airline employees, but we do have quiet power. We, with our screens turned towards us and away from the passengers, can move seats around to accommodate or annoy people as we see fit. We try to make it smooth, we try to make it soft for them. A soft takeoff. A soft landing.

The woman came running towards the gate waving paperwork in the air above her head. She had a small dog on a leash who was doing his best to keep up. He actually seemed to be enjoying the run, tongue out and panting all the way.

She said that the ticket agent had said that there was a problem with the dog’s paperwork. He hadn’t had one of the required vaccines. She said he didn’t need them, that they were going to a place that didn’t require vaccines for dogs. But the airline required the shots, I explained to her. To get on the plane. To make it safe for the humans, not for the dogs.

The woman left with her dog tucked under her arm. I think I heard her crying. I started to go after her but a flight attendant came down the ramp and pulled the gate door shut behind her. The plane left.

Anonymous

Rincon was my whole life, at least my life in the United States. But in my home country, I had three children. I had. Two of them are gone now, one I saw go down to the ground in agony, and the other disappeared right from his dorm at the college. There is only one left, my son, age twenty.

My last baby is in jail now. He has sent me a message that he can get out, but only tomorrow and only if I bring the amount of money he has told me which for my country is a month’s salary but in the U.S.A. is not very much. They say it’s a fine but of course it’s a bribe but there’s no difference if it’s a payment for a life. My son says they will not shoot him, but if I do not get him out tomorrow they will transfer him to a prison and no one survives there, even if you can figure out where he is it will be too late.

I took the money out of the bank and grabbed Rincon and his food and his papers and I went right to the airport. I bought a ticket for the next plane to the capital to get my son.

Rincon was a good dog. He was the only friend in the United States I could tell all my secrets to, including what I had to do to get out of my country and into this country. What I had to say to the lady at the border was true but also ugly. I only had to tell the border lady one of my stories, and the rest I kept until I could tell them to Rincon.

I told him the last story about how he was saving my son.

After I said goodbye to Rincon, I bought another ticket to my home country at a different ticket counter and left late that night and by the morning I was standing in the office of the jail and trading the rest of my money for a young man who looked tired, and for the first time ever, grateful.

Jill Bronfman was one of 12 Aspiring Novelists Selected for the Irish Writers Centre Novel Fair 2025, was the Barnes & Noble, National Essay Contest Grand Prize Winner, placed second in the Joan Ramseyer Memorial Poetry Contest, was named a semi-finalist for both the James Applewhite Poetry Prize and The Waking’s Flash Prose Prize, and received an honorable mention in the Storm Cellar Force Majeure Flash Contest. Her work has been accepted for publication in five collections and over thirty literary journals. She has performed in The Bay Area Book Festival, Poets in the Parks, The Basement Series, Page Street, Washington Square Annual Livestream, and LitQuake, and had her story about a middle-aged robot produced as a podcast by Ripples in Space. She has been accepted to residencies and conferences including Looking Glass, WonderMountain, and LitCamp. She is a reader for The Masters Review, and a Poet-Teacher for California Poets in the Schools. She volunteers with 826 Valencia and ScholarMatch helping kids write poetry and teens write their personal essays for college applications.

‘Climate Change’ Contest Finalist

Arria Deepwater (she/they) identifies as white, invisibly disabled, queer and faithfully middle-aged. Her work appears in In Between Spaces: A Disabled Writers Anthology, and she runs a newsletter, “Together, Between Worlds,” offering notes on a bad breakup with modern society. Arria shares a home by a lake with her mother near Perth, Ontario, Canada on unceded Algonquin Omàmìwininì Territory, where they regularly remind each other that they can, in fact, live without a dog. www.arriadeepwater.com

Michael Moreth is a recovering Chicagoan living in the rural, micropolitan City of Sterling, the Paris of Northwest Illinois.

Climate Change

Runner Up Spring Short Fiction Contest 2025

We run ahead of the sun as it travels around the house. It isn’t always this bad; it won’t always be this hot. But maybe we can’t count on that anymore. This particular heat wave, eager to aggravate everything it touches, appears to enjoy its reputation as a sign of increasing climate instability. In response, tendrils of illness, like sleeping dragons, turn restless and edgy beneath my skin. Mom’s not comfortable either — which inevitably means heightened anxiety — feeling wordlessly hunted by the sun as it traces the shape of our lives.

The big windows at the back are the first to be drawn, shades and slides adjusted according to the amount of sun and breeze. No more than an hour later (oh, please God, no more than an hour later), it’s close the window over the sink, lower the sheers, and adjust the blind on the rear-facing window in the sun porch. Then around we go. Tend to the next set of windows, reset the last if the sun has moved on and the air outside has lost its dull throbbing haze. Blinds, screens, sheers, sun, shade, breeze. And always the fans. Yes, always the fans. The fans are always on and, for Mom, the fans are always a worry.

They will use too much power. They will burn out. They are making an alarming noise. They will come loose from their fittings and fall on our heads. I feel painful and sluggish, with blood pressure that slumps through the day, and my throat is sore — which is never a good sign. The world slides sideways, sometimes slowing into a fuzzy haze, even when I don’t move my head too quickly. My stomach tightens and loosens erratically according to its own rhythm and a fatigue runs like thick syrup through my muscles and my mind. So maybe it’s my

own sensitivities causing me to feel like things have changed — like the tangled balance in which we 1

live has shifted — but I swear I can see a different pattern rising to the surface, and in the heat it’s hard for me to focus on it. Whatever is going on with Mom is a mirage, wavy softness distorting reality. She notices it too. We talk about it without talking about it. Acknowledge it without identifying it.

“The crows, or whatever you call them, are making a lot of noise.”

Or whatever I call them? When did Crow become an uncertain thing?

“Are they arguing about something?” I ask tentatively, extending the question across the length of the house like a lifeline, hoping that encouraging her to talk about it will help one of us find our bearings.

“I don’t know. There’s a whole lot of them gathered on the lawn by the road. I can’t see what they are doing. What do you call them?”

Okay. No longer certain what a crow is.

Careful now.

I pull myself slowly from the chair and walk stiffly towards the window where she is standing. “Yep. Those are crows for sure.”

She’s moving her head in short bobbing nods, her eyes fixed on the ragtag huddle of glossy black birds. They appear to be sweating in the heat with the rest of us. I can’t tell what the fuss is about either; maybe they are just cross because of the weather.

“Crows.” She says it reassuringly to herself. “In BC there were more ravens.” This last part spoken to me. Daughter-as-anchor.

“Yeah, that sounds right.”

“I only ever saw crows growing up. I don’t think there were ravens in Toronto.”

More certain now.

“Well there were probably some around somewhere, but you’re right, in Toronto we saw crows.”

More nodding, brows furrowed.

“What are those other black birds we have around here?”

And there it is. She hasn’t entirely lost touch with Crow. It has simply begun melting into other black birds.

“Grackles.”

“Cackles?”

“Grackles.”

“Crackles?”

“Guh - rr - ackles. Gr-ackles.”

“Grackles.”

“Yes. Grackles.” That’s not going to stick. I make a mental note to track what may be the ongoing disintegration of Crow, the repeated need to evoke Grackle. To watch and listen for the moment both birds lose all form.

It’s just after lunch. My clothes cling to me with damp and weariness. I can no longer tell the difference between the ambient heat and a hot flash. Time to pull back the sheers and open the window over the sink, close the windows and tilt the blinds all the way up on the side of the sun porch that faces the neighbours, and test the heat levels on the main windows; but probably leave them closed for another hour. Mom keeps repeating the phrase “a wall of heat” like an denunciation. I’m not sure if it’s the anxiety punctuating her responses or her memory fraying, but she seems perpetually surprised, vaguely offended.

We ate at the picnic table under the cedars. There are tiny tentacles of cool darkness that slink up the bank of the river and through the bush to lick at our ankles and the backs of our necks as we sit. Things are almost bearable. I return to the table with the mancala set.

“Someone needs to check the blinds.”

“I did that while I was in the house, Mom.”

“Did you?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure?”

Breathe. Keep your vocal cords relaxed.

“Yep! Do you want to go check?”

“No,” although she sounds incredulous. “What about the big windows? You didn’t open them did you? It will still be like a wall of heat.”

“No, I left them. We can check them again when we are done with our game.” My recent efforts to teach her mancala may prove futile, but she seems to enjoy the challenge. This will be the fifth time we play in the past several days.

“Should I help you at all this time?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure?”

“I won’t remember anything if you don’t help me.”

The game is scattered and disorganized. She makes several astute moves without my help, but she also gets confused more than once, and counts wrong several times. Early on in the game she looks at both our home-troughs and notices that I am in the lead. She rests the tip of her knobby finger on her trough and says definitively, “I have three!”

Sometimes my abject lack of certainty as to how to respond helps. In that space, sometimes humour inexplicably erupts and engulfs us — and she is still in on the joke. Something in the compassionate cosmic math of the universe resolves to “x equals funny,” and we laugh. Huge, breath taking, whole-body, tear-inducing laughs.

When the sun dips below the treetops on the other side of the road, we open everything on that side of the house. Tonight, we do this early because there are clouds glowering and the breeze has matured into a full-sized wind. We are wet from a soak in the river. It’s not chilly, but it cools us down. I’m making my way from room to room trying to let the house take a breath.

“Do you want me to move the dehumidifier?”

This is shouted from the basement. Does she even know where I am? How did I become the authority on temperature and humidity levels?

Should I ...?

Do you want me to ...?

Little words that signal such loss of agency, a transition of power. I don’t want it. Maybe it doesn’t mean that at all. Maybe it’s a loss of focus and self-assurance. Maybe she can’t remember when we last shifted the dehumidifier to the other room in the basement.

“What do you think?”

A beat. I slide the bathroom window open wide. Another beat. I pause in the hall, not wanting to go into her bedroom where I won’t be able to hear her. A third beat and I lean towards the stairwell, “Mom?”

“Yeah?”

“What do you think about the dehumidifier?”

“Does it need to be emptied?”

My mind runs the algorithm of likely possibilities given the known variables, uncertain as to how to account for the unknown. Uncertain as to what might be slipping from her mind, like the river water drips from her hair down the back of her neck. I stall because I honestly don’t know if I can handle the stairs.

“Is the red light on?”

The moment stretches a little too long. Is she searching the face of the beast? Trying to find its beady red eye.

“No.”

She sounds reasonably confident.

“Well, maybe it would be good to empty it anyway, then leave it where it is overnight” “It doesn’t need to be moved?”

It might.

“No. I think it’s okay where it is.”

The storm starts around 4 am. I wake up to the wind howling. A strike of lightening hits so close I hear it sizzle, thunder exploding like a world rupturing. Every window but my own had been shut before bed. (What if it starts raining and we don’t hear it?) As the rain falls like a million ballbearings I drag myself out of bed and crank the window closed. Her door flings opens and I can hear her lurching forward, sock-padded feet hitting the floor with clumsy urgency. She passes the bathroom and my own door, moving into the back of the house. I move faster than I should — faster than my body would like — until I’m standing with her by the outside door, her hand reaching for the lock.

“Mom?”

She jumps. Panic swirls beneath the surface of her face. Maybe she’s not fully awake yet. Maybe she is, but everything is jumbled and tossed with the storm. The rain pounds the house, more lightening and thunder, and then she blinks.

“Are the windows all closed?”

Her voice sounds far away and small, but I go with it.

“Yes, we did that before bed.”

“Even yours.”

“Even mine.”

She sighs and relaxes, leaving me a bundle of jittery tension, veins filled with adrenaline and thwarted rest. We decide to sit on the couch and watch the storm for a while. The power flickers a few times, the roof creaks as if to ask how much longer it will have to put up with this, and the tree branches slash through the air, batting at the rain. After almost an hour the lightening and thunder fade into the distance, the storm inhales deeply, and the wind unleashes itself. As soon as the sun’s up, the phone calls and visits begin. Neighbour checking on neighbour. The storm flipped over a few docks and pulled boats from their moorings up river. Trees are down, a few windows broken, things that were meant to stand up-right have tipped over, but everyone is safe.

“We’re going to have to borrow Bill’s ladder. The wind started to pull the siding off the house by my bedroom.”

Did it?

Yes, as it turns out it did.

Bill’s ladder is an handy thing — compact and extendable — but heavy as a dead body. The siding isn’t too unco-operative about being cajoled back into the joins and my symptoms are just manageable enough, but my job also includes randomly checking to ensure that Mom is holding the ladder steady. At one point, I look down to see her leaning casually against the left runner, her attention captured by something in the middle-distance.

“Mom, I need you to stand directly at the foot of the ladder.”

“What do you mean?” She looks up, searching for clues in the sun-bleached blue vinyl. Aware of the soles of my feet pressed into the step, the palm and fingers of my right hand wrapping the rounded top of the rail; steady but not tense. My left index finger scrying a direct line to the foot of the ladder. Vocal cords loose, face open, breathing even.

“Please turn to face the ladder, put a hand on either side, and lean towards it.” “But its fine.”

An image of the unevenly graded lawn ripples through my sternum.

“Mom.” Slightly more authoritative. “I’m two stories up. I need you to move into position in front of the ladder and brace it evenly, please.”

She shifts her body, her expression petulant, “I was paying attention. I would have moved if the ladder had started to slip.”

Yeah, because that always works.

Now happier, more eager, “I should be the one up there. I like climbing.”

I turn back to the siding, not sure how my words will land, “I like the climbing just fine, it’s the falling I have a problem with.” They hit their target and she giggles. Thrumming pain moves around my body in a pattern only my neuroreceptors can track, tingling ghosts linger in the space it leaves behind. My head feels like a world attuned to its own rules of gravity. Like a lead balloon floating, barely tethered to the top of my spine. I’m aware of every muscle; in constant negotiation with my center of gravity. I breathe. I think of Mark, the guy who used to be our handyman. The guy who monkeys up tv antennae and sashays across rooves as if he trusts what his muscles will do with the orders he sends them. As if his body will know where it is in space and how to move through it without faltering.

“While we have the ladder here, we should wash the windows!”

Fuck me.

“Mother!” Keep it playful. “Just so that you know: Your daughter is up a ladder with M-E, fixing shit while her meds are wearing off.”

“Oh no! Okay!”

It worked. We’re laughing again.

“I’m fixing the siding, getting down, and this ladder is going back. Yes?”

“Yes!”

“Okay?”

“Okay!”

Good.

None of the neighbours mind the clean-up given that the air feels light and the moisture rising from the sodden soil is cool and quiet. We trade encouragements like playing cards, each trying to collect enough for a winning hand.

“At least the heat has broken!”

“I’ll take the hassle over the humidity any day!”

“That storm was a close call, but worth it for this!”

But by noon our optimism begins to wilt and go soggy in our sweat-soaked hands. The humidity rolls back in like a fog, dense and heavy, and the sun reasserts itself in the sky. Moved by forces bigger than ourselves, Mom and I try to keep pace with it. Blinds, screens, sheers, sun, shade, breeze. And always the fans. The heat will break eventually and when it does, I will need to gather my strength and talk to Mom about what’s happening — acknowledge the changes coming to us. But not today. Today we’ll just try to stay ahead of the sun.

Arria Deepwater (she/they) identifies as white, invisibly disabled, queer and faithfully middle-aged. Her work appears in In Between Spaces: A Disabled Writers Anthology, and she runs a newsletter, “Together, Between Worlds,” offering notes on a bad breakup with modern society. Arria shares a home by a lake with her mother near Perth, Ontario, Canada on unceded Algonquin Omàmìwininì Territory, where they regularly remind each other that they can, in fact, live without a dog. www.arriadeepwater.com

‘A Game of Chess at Midnight’, ‘Poem’ & ‘Blind Date’

Chase Harker is a poet from New Bern, North Carolina. He is currently a student in the MFA program at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His work has previously appeared in Flying South, BarBar, In Parentheses, and elsewhere.

Heather Holland Wheaton is a writer, photographer, actor and tour guide. She’s the author of the short story collection, You Are Here and her work can also be found in Shooter Literary Magazine , Press Pause Press, Red Noise Collective, Slipstream, The Morning News and Every Day Fiction. She lives in Manhattan and will never leave.

A Game of Chess at Midnight

They are so much like the dead,

The chess pieces plucked, one by one,

From their squares and set

Along the edges of the board.

From the shade of an opponent’s hand

They watch the match play on.

They witness their deaths in others.

Like bare, meat-picked knucklebones

The white pawns glisten beneath

An electric flame. First to fall,

They are toys for the proud

To flaunt with swivels,

Or gyre together between

A few cruel fingers.

I have seen a marble bishop

Roll off a table and shatter

Into fragments finer than dust.

I have glued a crest back onto

A wooden horse then checked

A king in a three-prong fork.

The moves of the dead are recalled

By those alive in the field,

Those who have become the frontline.

In the end, each graveyard is plowed,

Limbs are reattached to torsos, torsos

To heads. Arranged in rank order,

A coin taken off an eye is flipped

For white or black.

Poem

After the late night

thunderstorm

observe:

at dawn

the backyard

thick with raindoves

and squirrels

foraging,

side by side,

for nuts

wind-

shaken

from the branches above.

Consider:

how quickly

they all scatter

when the house cat

leaps loose

from the sunroom.

Blind Date

she left

so soon

i was not

able to

tell her,

over

California

rolls,

the price

of eggs

in China.

Chase Harker is a poet from New Bern, North Carolina. He is currently a student in the MFA program at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His work has previously appeared in Flying South, BarBar, In Parentheses, and elsewhere.

‘Leaving Crawford’

Max Talley was born in New York City and lives in Southern California. His writing has appeared in Vol.1 Brooklyn, Atticus Review, Santa Fe Literary Review, Litro, and The Saturday Evening Post. Talley's collection, My Secret Place, was published in 2022 and When The Night Breathes Electric, debuted from Borda Books in 2023.

Dylan Hoover (he/him) is a fiction writer from Erie, PA. He graduated in 2023 from Allegheny College, where he earned a BA in English and Creative Writing. During the heart of the pandemic, he studied abroad at Lancaster University in England. There, he unearthed interests in British culture, as well as a passion to write historical fiction. Dylan’s fiction has appeared in Wilderness House Literary Review, and his forthcoming photography in Great Lakes Review. He currently is a second-year MFA student at the University of New Hampshire. Instagram: dylhoov96

Leaving Crawford

Megyn Griffin relished her early mornings at the front desk before guests wandered in for breakfast. She could gaze out toward the rolling hills and await the rumble and horn blats from the first train of the day. Many more followed, masked by traffic noise, but the first brought everything back into focus: another morning in Crawford, Arizona. Situated just off I-40, it sat near Williams. That little city had dubbed themselves the “Gateway to the Grand Canyon,” their old-fashioned downtown bustling with tourists.

Crawford, on the other hand, was the “Gateway to the Gateway.” Smaller by half, it relied on visitors who preferred lower rates and less kitsch, and the dazed interstate drivers who could not endure another highway mile without rest.

Coffee vapors steamed up around her face as Megyn studied a science book, aware that she was eighteen and a year behind on college plans. The delay? Her mother needed help to run the Mountain View Motel.

A stern biker deposited his metal sand bucket ashtray by the office's desk. “See you next trip, young lady.” He headed for the raven-haired woman waiting on the back of his Harley.

Megyn was a young lady in Crawford. Maybe seventy teenagers, several dozen folks in their thirties or forties, and the majority of the population ranging from age sixty to death.

She mouthed pleasantries to the guests checking-out, consciously skipping the free continental breakfast of spotted bananas, Wonder Bread with butter pads, and sweaty gray sausages lounging in a metal serving tray.

Their utility guy came inside to stamp his feet. Still chilly in early April, dirty crusted snow on sidewalks, while larger pristine patches flecked green mountains in the distance.

“Hey, Meg.” The steam of his outdoor breath dissipated in the heated interior. Brandon Carter was twenty, handsome, and a complete fool. Megyn had known him most of her life. Attended school together, made-out once three years ago, but she'd moved on. Megyn planned to go to college, then become a teacher or a nurse in a big city, while Brandon held delusions of Hollywood stardom.

Due to the scarcity of others in their age range, and since both were considered attractive, every Crawford adult had asked, “When are you two kids going to get together?” The gossip-starved neighbors were desperate to live vicariously through them. Megyn shrugged it off and only Brandon's continued eagerness bothered her.

“Thought about my proposal?” He yanked at his jacket, shaking off the cold.

Megyn laughed. “You were joking, right?” She slapped the guest book shut. Despite a computer in the back, they still signed travelers in by hand. “I'm too young.”

“I meant engagement for a year or two first.”

“Not getting married until I'm thirty, or near.”

Brandon lifted his baseball cap off then pressed it back on in frustration. “But it looks good on paper. Everyone says I'm the hottest guy in town, and when your braces are off, you'll be maybe the sweetest girl around.” His face soured when she laughed. “Why didn't you get your teeth fixed before?”

“They got really crooked at sixteen.” She eyed him. “What's your big rush anyway?”

“When I make it in Hollywood, I should have a wife. To seem regular to the public.”

“Seriously?” She snorted. “The answer is no.” Megyn switched to business mode. “There's a toilet clog in unit seven.”

He kicked a cowboy boot against the base of the office desk in frustration.

“Dude, please chill.” Megyn went to wipe down tables in the cramped dining area. “Anyways, everyone knows you're seeing the hag.”

“Don't call her that,” Brandon said. “Wendy Haggerty, and she's only fifty.”

Megyn didn't reply since fifty hit folks harder in the southwest. The spring winds, dust storms, and sunny, dry-ass climate were brutal. Another reason she planned to bail. People needed moisture, to sweat, have oil in their pores, or they'd wither and wrinkle away. Cigarette smoking didn't help Crawford residents look young either. So, a small population of baby-faced youths existed amongst grizzled elders with tales of the good old factory days. Megyn knew nothing of the factory, beyond that its demise had left a wake of bitter, desolate souls forever mumbling about it. Crawford was a ghost town in the making, haunted by humans in denial of the end being in plain sight.

“I'd drop Wendy the minute you agree.” Brandon waited for her reaction. “I was planning to end things soon anyways.”

Megyn turned from cleaning. “As if you're calling the shots.”

He grabbed the toilet plunger from behind the desk. “When you see my face on that billboard west of town, you'll be sorry.” Brandon slammed the office door behind him.

Megyn collected the departing guests' key cards. She was viewing colleges in Colorado on her laptop when the door bells jingled.

“Is it noon already, Mom?”

“Call me Candy,” her mother said. “I might be near fifty but I plan to remarry. Best not to reveal attachments right off.”

“Wow, I'm an attachment now.” Megyn gazed up from her screen. “You'd have to move to Flagstaff to meet anyone decent.” Her father died seven years ago at age forty-eight. Possibly cancer from working at the chemical plant in Joseph City. Candy wouldn't talk about it. The settlement paid off the motel, and that closed the book for her.

“There's eligible men around.” Candy sighed. “I'd just need to lose twenty pounds, get my hair done,” she stared outside, “and drive over to Ash Fork for weekly facials.” She shuddered. “I look older than my age.”

“No you don't, Candy.” Megyn hugged her mother, who often needed reassurance. “And stay away from Vern's Beauty Salon. She does permanent makeup stuff and gives brutal acid skin peels she isn't trained for.”

“Vern told me she has a cosmeceutical license.”

“Bet I can print you one of them from the internet right now.” She gathered her laptop, coffee mug, and books. Her mother worked noon to seven, then Megyn spelled her until the front desk closed at ten p.m. On Sundays and Mondays, her high school friend Skyler stepped-in so Megyn could have two days off.

Not in a rush to do anything, Megyn slumped on the iron furniture set on the office's porch. The sun shone and it felt near sixty, but she kept her lined blue jean jacket fastened. High in the pine-covered mountains, they got some water from the snowmelt. It might hit 90 in the summer, but never the 110 degree hell of the arid plains and desert surrounding Phoenix.

When the familiar sputter and hum of a vintage Ford F-1 pickup approached, she didn't have to look up.

“Hey, young lady. Need a ride? Not that there's anywhere to go in this godforsaken shithole.”

Cole Jepson, the only local that Megyn admired. Tragic, him being fifty-six, but she'd adopted him as her uncle. His hair a wild tangle, thick and graying, with a gritty beard sprouting on his chin. He looked pummeled by life, but had once been something. Blue eyes still clear and boyish despite the weathered face. The fact that his book of poetry was published by a New York publisher in his thirties was what impressed Megyn. Crawford didn't have celebrities, but he was a notable person. Educated. Spoke in clear sentences.

“Sure.” She hopped in. “Take me to the DQ.” Across the railroad tracks lay the derelict east side of town. Mostly shuttered businesses and tumble-down homes. Leftover reminders of Crawford's past.

They reached the Dairy Queen's deserted lot and Cole parked. Megyn stared at the hollow structure, the frame and insignia still there. She could close her eyes and imagine the ice cream flavors, being driven over by her mother when she was younger. “It's so weird,” she said, “to feel nostalgia when you're still a teen.”

Cole laughed, pushing a mess of hair back from his brow. “Never cared for it myself.” He squinted toward a barren, weedy patch of land with a damaged screen rising above it. “I do miss the drive-in though. That was a blast, back in the day.”

“I barely remember it. Closed when I was ten, I think.”

“But you've been since then...”

The abandoned parking lot served as a make-out spot for high school kids. “Well, maybe once or twice.”

“Who can blame you?” He rustled around in his seat. “Hope you're still—”

“Leaving Crawford? Hell, yes,” she said. “Waiting on three colleges. They send acceptances soon.” Megyn noticed Cole's mouth twitch like he knew what she was about to ask.

“Why did you come back? I mean, New York City. You were published, gave readings, could have been a poetry teacher at Columbia or some liberal arts college.” She gazed at him. “It kills me being here, and I'm not even nineteen.”

“New York scared me,” Cole replied. “I couldn't take it.”

“You? You're not scared of anything.” She shook her head. “I saw you bounce that mean drifter who wouldn't leave the Mountain View.” She tapped his hand. “And when a steer got loose on Main Street. Who cleared it off? Not our useless sheriff.”

“That's different.” Cole played with an unlit cigarette. “I can deal with things, one on one. New York is filled with people, buildings, streets, cars and buses, voices crying out. Pent-up emotions and frustrations and violence coming from everywhere.” He raised his fists like a boxer. “I couldn't fight it. Sapped my energy.” His head bowed. “Guess I'm a coward.”

Megyn punched his shoulder hard. “You are not. Go write some new poems. I read your first book all the time. You have talent. Just need to get out of Crawford.”

He coughed. “Nah, I'm a blown gasket.”

“I am not listening.” She cranked open the passenger door and jumped out. “I'm walking home from here.”

“Hey, wait.” He puttered the old Ford along beside her.

Megyn put on headphones and blasted the music. She waved Cole on ahead by the hulking closed factory. It once made wire hangars and metal hooks and nothing that made any sense to a teenager in the 21st century.

Brandon finished his duties by two p.m. Hammered window screens back into place, plunged two toilets, and added touch-up paint outside the motel units. Left him four hours to kill.

The Mountain View had created two-room suites in the smaller side of the L-shaped building. More expensive but they'd become popular. At six, Brandon served drinks in the outdoor patio area until seven-thirty. Possibly illegal, but the local police chose not to interfere. Candy was trying to bring tourists into town, who would stay at motels, buy food at restaurants, overpriced gas, and be given parking and speeding tickets. It would be anti-business, against Crawford's survival to enforce the letter of the law. Brandon claimed to be twenty-one so he could bartend.

A Los Angeles film producer was staying in a suite, with two female assistants in the adjoining one. Yesterday, Simon Maybank told Brandon he had natural good looks and vaguely resembled a young Tom Cruise when he smiled. Simon wanted to talk more tonight after he returned from scouting film locations.

Brandon pressed Wendy Haggerty's number.

“You done for the day, slugger?” she asked.

“Yeah.” He never knew what to say to her. “What's going on?”

Wendy laughed with a whiskey rasp. “Nothing. Be at the semi-trailer in thirty.”

“Do we have to meet there?”

“We can't go to your parents' place, and Gil's around here,” she said. “He might not walk anymore, but his hearing is good.”

“Yeah, okay, I just thought—”

“We have to be discreet.”

“Everybody in town knows, Wendy.”

“See you soon.”

At seventy-one, Gil Haggerty had suffered two strokes in the last years. The second requiring a wheelchair and an attendant to bathe him. Gil's wealth allowed his purchase of acreage on the north side of the interstate a decade ago. His initial plans to raise crops or keep livestock failed, due to the hilly terrain with dramatic rises and falls. Not good for planting, while cattle preferred to graze on level grassy fields.

Halfway up the highest rise of his property on the western border of Crawford sat a semi-trailer. The cargo compartment from an 18-wheeler Gil owned. Across its metallic flank, painted in seven foot letters was: TRUMP 2024. It had been propped there since it first read 2020. In whatever direction one traveled on the interstate, this mammoth container and its message were clearly visible.

Brandon drove his Toyota pickup along the winding tread that dead-ended behind the semi-trailer. He wet his dark hair back with bottled water, then knocked on the loading doors.

“It's open,” Wendy yelled.

Inside, lay a queen-sized mattress. A dim battery-powered lamp glowed while a boombox played maybe Whitney Houston or Mariah Carey. Brandon didn't know old pop music. Wendy was propped on an elbow in her underwear. She drank Jack Daniels from the bottle. “Let's get going.”

Brandon stripped. Wendy Haggerty possessed a stunning figure, something out of 1950s films, curves jutting in every direction. Her body was legendary in town, provoking gasps and stares of wonder—even from young children. However, something happened to her face. The baby fat had drained away, highlighting her father's wide flat nose and her mother's lantern jaw. Now, her eyes appeared sunken into their sockets, and they showed a combination of rage and fear, as if aware they were sinking.

Brandon kneeled onto the mattress edge. “Feel like talking first?”

Her face reddened. “Do locals call me... the hag?”

“Nobody says that, not around me.” Just a white lie this time. Brandon reached a hand out to caress her.

“Don't!” She rolled over. “Okay, let's get going.”

Brandon had been confused. Sure, he liked women, and planned to marry a normal pretty one, soon as Megyn agreed. But lately, he'd been watching cowboy movies on TCM while he worked. He wanted to know those rugged, lanky men, ride horses with them, share a bunkhouse. At present, he could stare at Wendy's shoulder blades and abstract it. He closed his eyes, imagining crisp blue jeans and shiny leather saddles.

“That's it?” Wendy craned her neck sideways. “Well, save the rest for your little girlfriend down at the Mountain View.”

Brandon dressed quickly. “She's not my—”

“I don't care.” Wendy covered herself with a sheet.

Brandon wandered out to the Toyota, blinded by the sudden blast of afternoon sunlight. The peak of his life; he deserved better.

Arriving at the Mountain View just before six, he put on a clean white shirt, a bolo tie, and a dark server's vest. Then he mixed drinks on the terrace fronting the motel's deluxe units.

The producer, Simon Maybank, entertained two older German couples on outdoor furniture padded with pillows. When the couples trekked off to Crawford's center for dinner, Simon beckoned Brandon over.

“Foreign investors,” he whispered. “I'm always raising money. You know, films aren't cheap.” Simon signaled his assistants and they retreated into their suite.

“So you're a producer?” Brandon sat at the edge of his seat, chest jutting forward.

“Producer, director, location scout.” Simon studied Brandon while finishing a Vodka Collins. “And what's your plan?”

Brandon coughed. “I want to star in a franchise, like Harrison Ford did with Indiana Jones.”

“Really? Who would your character be?”

Brandon flashed his dazzling smile. “Zack Bone, a gym coach by day, but after PE class, I put on a cowboy hat and become... Eldorado Bones.” He glanced over for affirmation.

Simon winced, head tilted slightly. “You did go to high school and maybe Crawfish College, right?”

“I'm just twenty-one, but I graduated Ash Fork High last year, in the top 100% of my class.”

Simon grinned. “It's getting dark. Why don't you clean up the bar then we'll talk in my room.” He refilled his drink and vanished within.

Brandon rolled the bar cart on wheels across the main street, setting it back into the motel office. Megyn looked up from her studies and stifled a laugh at his outfit.

“I'm onto something,” he said. “Listen, can we meet tomorrow?”

“Not another proposal.” She rolled her eyes.

“No, just to hang out. Remember years ago, we'd watch the trains go by at sunset?”

“When you got me high and tried to—”

“No.” He sighed. “I just wanted to talk like we used to do.”

Megyn flattened her book open on the counter. “Sure, okay. Nothing else going on.”

Outside, Brandon primped in his Toyota's rearview mirror before knocking on Simon's suite.

“Come in.” The producer reclined on his king bed, barefoot and wearing a silk bathrobe. “Make yourself comfortable.” Four candles burned in the dimly lit room.

Brandon perched on a chair, keeping his chin thrust out, as he'd practiced.

“So this is how Hollywood works,” Simon said. “You do extra parts, non-speaking, then you get a line, maybe two. If you move right and speak well, you could get a character role for some screen time.” He paused. “With adventure scripts, the way in is as a stunt man. If you can survive flaming car crashes without sustaining heavy bodily damage, then you're a shoo-in for an action movie.”

“I couldn't find any of your films on Google.”

“Ever heard of Fast and Furious?”

“You produced those movies?”

“No, Slick and Serious, the knock-off series. Huge in Taiwan and Jakarta.” Simon tugged at an earlobe. “Anyway, someone has to put in a good word for you. You do something for them and they help you out in return, right?”

“Yeah, I guess...”

“For instance, I could use a back massage.” Simon untied his bathrobe.

Brandon turned away. He'd played sports and showered with the team, but never seen a man so pink and hairless—it confused him. Maybe Brandon just liked cowboys.

“What's the matter?”

Brandon shuffled toward the door. “I need to consider things.”

“My card is on the table. Call me, but only when you're ready.”

Megyn finished her shift all tangled-up. She had wanted to ask Cole to go sit atop the water tower at dusk and watch the first stars appear in the night sky. Cole had never acted weird with her since she turned eighteen, but what if he did? How would she gently say no without ruining their friendship? And what if she felt cold after sunset and leaned on him, giving him a signal. She was mixed-up and needed affection, or at least understanding in a decaying, lonely town. Cole might go along if she started something and that would be awful. Or he might fend her off and then she'd feel mortally insulted. Or worse, they might just sit there. So she couldn't ask him to join her, and yet there was no one else to ask. Skyler would only tag along if a beer or weed was involved. She didn't understand starlight, poetry, or anything important.

The door bells jingled at noon when Megyn expected her mother.

Instead, Cole stood there grinning. “Thought we could drive over to Ash Fork, get you lunch, and well, breakfast for me.”

She moved her mouth around her braces. “I'm real busy with college stuff.” She couldn't make eye contact. “Maybe it's best to skip our adventures this spring. Distracts me from studying.” Megyn gazed up. Cole had already turned away, but she could tell by his sagging posture she'd hurt his feelings.

The pickup truck's engine faded to the west, and she wiped away tears when Candy came to spell her.

“What's wrong, darling?” Candy embraced her. “Did Brandon Carter insult you? I will slap some ugly into that dumb-ass pretty boy.”

“No.” Megyn sniffled. “What if I get stuck here forever?” She didn't mention the rejection that came in the morning mail.

“You're almost nineteen and those three colleges will be fighting over you.”

Megyn slept the whole afternoon then took a sick day the following morning. Imposed a 24-hour delay on Brandon's “let's hang out” plan, because who cared when they met? Every day felt the same in Crawford. A total bummer.

Just before six when Brandon was due, she ran west to the Grand Canyon Tavern. Make things right. The vintage Ford sat parked just outside. Underage for a bar, she tapped on the frosted window of the historic tavern until she got Cole's attention.

He shuffled out, expression stern. “Never interrupt a man mid-beverage.”

“Just wanted to talk for a sec.”

“I brought something for you inside my truck.”

Megyn slid into the passenger seat.

“Wrote this poem last night.” He reached over her to the glove compartment. “Printed it out and everything.”

She tucked the folded paper into her pants' back pocket. “Write ten more.”

“Jesus. Tough lady.”

Megyn set the door ajar, preparing to dash. “You know Skyler?”

“Of course. She's, what do they call it, your bestie, your BFF?”

“Nope. She's my girl, my pal.” Megyn paused. “You're my bestie.”

Cole seemed startled, then frowned. “Buzz Skagmeyer might not like that.” He glanced toward the bar's window. “We been drinking together since long before you came around.”

Megyn gave him the finger, smiling. Then she thumped the top of the pickup goodbye and went skipping back toward the Mountain View.

Brandon's Toyota waited by the motel units. The film people had checked-out, so no bar set-up outdoors. “Don't you look all happy,” he said. “I thought you were sick yesterday. What, did Aunt Flo visit?” He laughed—alone.

“Let's go.” She jumped in and turned on the radio. “Just so you know, we're not fooling around or nothing tonight.”

“Jesus, you think I've got a one-crack mind? Hey, truce, okay?”

“Sure.”

Brandon parked near the strip of woods that bordered the railroad tracks. Trains ran hourly, except for a flurry between six and eight. He spread a blanket and unwrapped a tuna fish sandwich, then offered her half. He'd brought beers, but Megyn just wanted sips from his. The ground shook when a westbound cargo train rumbled by.

“We'll be better-off if McDonald's comes,” he said. “Maybe an IHOP too. Then a train station to bring more tourists here from the Grand Canyon.”

“We're twelve miles from Williams. They can't have stops in every little town.” Brandon's bottle rim tasted of tuna but she didn't care. Made it feel like camping out, roughing it. “Anyway, you're going to Hollywood. Did that producer—”

“He gave me his card.” Brandon stared away. “It's a weird world. But if I became a star, I'd come back to Crawford.”

“Why?”

“To show everyone who thought I was a stupid loser that they were wrong.”

“You want to be a movie star just for spite, to get back at people?”

“Yeah, of course.” He swigged his beer. “But I'd buy land here too. Make improvements.”

“A trailer-bed on every hillside?”

“Jesus. I'm trying to be for real tonight.”

Megyn punched his arm softly. “You are.” She finished eating.

Another horn sounded as an eastbound train approached. This one came slow, a jangle of ratcheting freight cars, the squeal of brakes. They watched it stagger along, passing them gradually. The line of boxy containers were rusty, discolored, graffiti-marked, and ugly as hell, but in that moment, the most beautiful thing Megyn had ever seen. She counted twenty cars. “I could walk along and keep up.” And she did just that.

“Hey, where you going?” Brandon trailed behind her.

Megyn jogged faster then jumped up on the edge of an empty freight wagon. So easy, so fun!

“Get off there,” Brandon shouted. “What about us?” His words were soon drowned out by the rattle and locomotion. Leaving a stick figure waving his arms.

The train accelerated through the pine tree dusk until she couldn't see him anymore. The clanking give-and-take of section couplings and metal wheel tremble overwhelmed everything else. As the dazzle of starlight showed overhead, she felt euphoric, totally high. Three-hundred bucks lay scrunched in her purse. Not enough for anything of consequence, but whether practice or a dress rehearsal for her eventual escape, she'd ride it through to Flagstaff. A few days there to clear her head. Unfolding Cole's poem, Megyn squinted in the dying light. Just seventeen words.

Leaving Crawford:

Right away, damn it. Sooner.

Don't you ever come back! (Like I did...)

Not never.

End

Max Talley was born in New York City and lives in Southern California. His writing has appeared in Vol.1 Brooklyn, Atticus Review, Santa Fe Literary Review, Litro, and The Saturday Evening Post. Talley's collection, My Secret Place, was published in 2022 and When The Night Breathes Electric, debuted from Borda Books in 2023. "Leaving Crawford" will be featured in Talley's story collection, Destroy Me Gently, Please coming from Serving House Books in June 2025.