THE EXHIBITION

•

THE EXHIBITION •

‘Giving Away the Kingdom’

Ryan Rahman is a writer based in Orlando, Florida. His previous works (all poems) have appeared in Beyond Words Literary Magazine, The Stardust Review, Half and One, BarBar Literary Magazine, and Humans of The World. When he’s not writing, Ryan enjoys reading, listening to music, watching movies, and traveling.

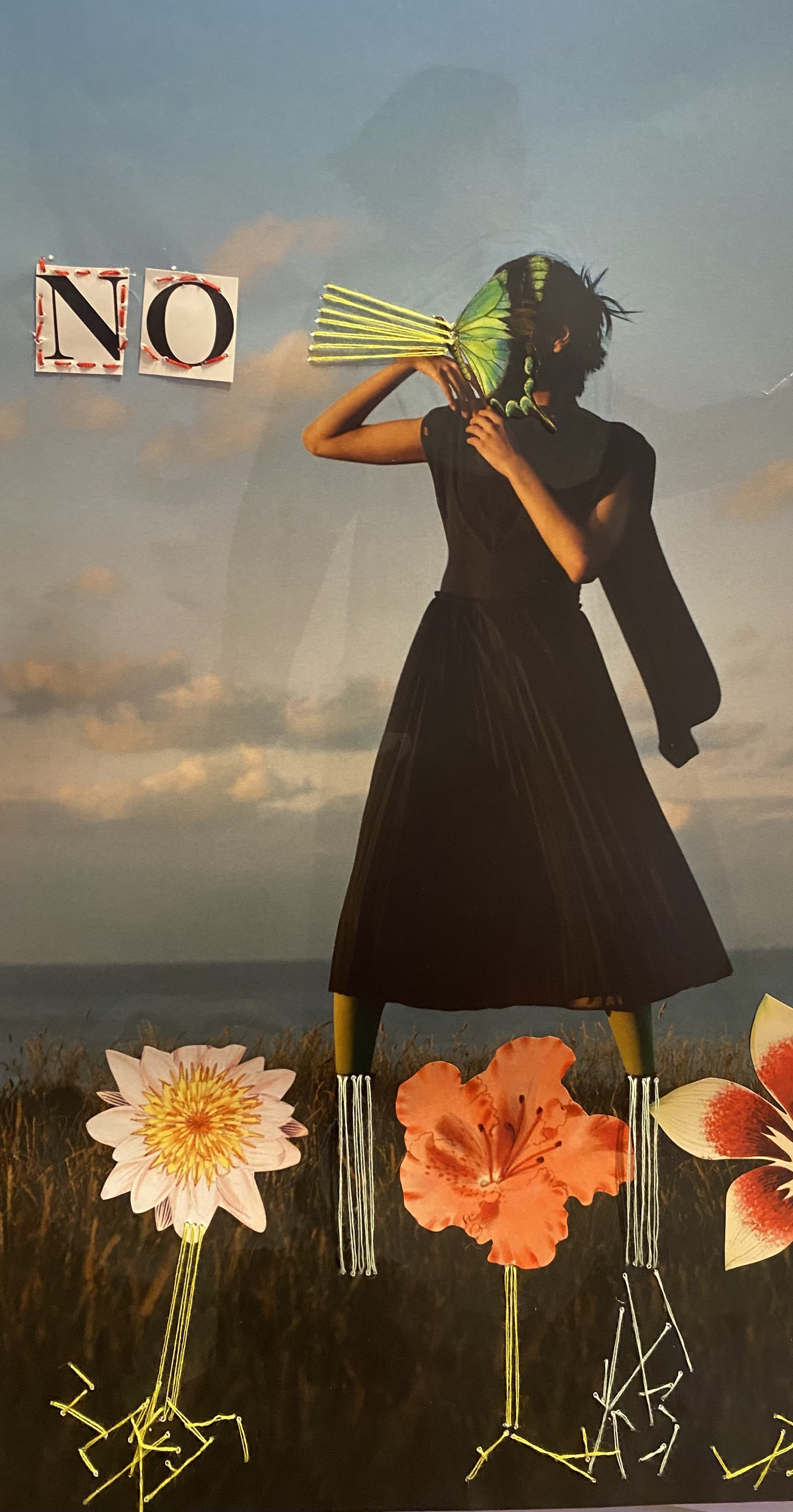

Shelbey Leco is a mixed media artist. Her style was heavily influenced by her grandmother growing up. As a child, when spending time with her grandmother, Leco enjoyed coloring in giant coloring books. Her grandmother soon realized that Shelbey went through art supplies rather quickly. So, her grandmother taught her the art of zentangle, by creating various patterns and shapes within negative spaces. Through time, Leco’s work developed more into mixed media, however repetition and pattern work is present in her work today.

Giving Away the Kingdom

The inept king does nothing—

Idle, detached, ignorant.

He sits on the throne, unmoved,

Odious and bungling,

A spectator to his kingdom’s decline.

He makes no effort,

No desire to restore

That which is broken.

As it all deteriorates,

Piece by piece,

Until nothing remains—

Only rot and ruin.

His covetous kin and sycophantic companions,

They thrive,

For they are powerful and persuasive,

Lacking even the tiniest shred of shame—

Profiteering and plundering,

Feeding him hollow adulation,

Satiated by their greed,

And his blissful oblivion.

It is the people who endure—

Voices silenced by indifference and apathy,

While he feasts,

Engulfed in his revelry,

Unmoved by their cries,

As the streets seethe with vengeance,

Thick with hatred, unbridled.

Everyone can see—

He is a fraud—

Impotent, disgraceful,

A willing enabler of decline.

He should be ashamed,

But instead, he is elated,

As the kingdom burns around him.

Unseeing, willfully blind,

He smiles with vacant delight,

Unaware of enemies closing in—

Some concealed, others apparent.

Exploiting the vulgar decadence—

Degrading what still remains.

Crumbling fortifications—

Tattered banners—

The inevitable collapse draws near.

When the kingdom falls,

His failure will be written in ash,

A stain on his lineage,

A blight upon the throne.

Someday, he shall be dethroned—

Until that day comes,

Crushed beneath the weight of negligence—

We bear the cost of his ruinous reign.

Ryan Rahman is a writer based in Orlando, Florida. His previous works (all poems) have appeared in Beyond Words Literary Magazine, The Stardust Review, Half and One, BarBar Literary Magazine, and Humans of The World. When he’s not writing, Ryan enjoys reading, listening to music, watching movies, and traveling.

‘Red Light’

Alex Passey is the author of the novel's Mirror's Edge and Shadow of the Desert Sun. His short fiction, poetry and journalism have been featured in many publications, most recently in the graphic novel Twilight of Echelon, the Apocalypse anthology from Dragon Soul Press, and the Winnipeg Free Press.

Shelbey Leco is a mixed media artist. Her style was heavily influenced by her grandmother growing up. As a child, when spending time with her grandmother, Leco enjoyed coloring in giant coloring books. Her grandmother soon realized that Shelbey went through art supplies rather quickly. So, her grandmother taught her the art of zentangle, by creating various patterns and shapes within negative spaces. Through time, Leco’s work developed more into mixed media, however repetition and pattern work is present in her work today.

Red Light

I traced my hand over the coffin, as if admiring the smoothness of the lacquered wood. Really it’s just because I never know what to do with my hands. But it seemed a sturdy vessel to spirit a person beyond this mortal realm, and would duly protect this vacant body from the soil and water which had given life to all things on this Earth. A bizarre death rite that I will never understand.

He’d asked for a closed casket ceremony, as though even now he preferred the privacy of a dark room to the scornfully inquisitive light of day. I wondered if the velvet upholstery of the casket’s interior would remind him of his plushy gaming chair if he were alive to compare the two. I wondered how long it would take for his sedentary body to spend as many hours in the former as it had in the latter.

Wiping my forearm across my eyes, I turned to leave. The tears were real. They always were.

“See you tomorrow, Scott?” the undertaker asked after me as I strode across the otherwise empty funeral hall.

I didn’t turn. I just raised my hand in confirmation.

“Great, see you then. And remember.” His voice pitched up melodiously then, in an imitation of the singer from Journey. “Don’t stop, bereavin’!”

He laughed like it was the funniest thing he’d ever said, even though it was at least the fifth time he’d made the joke. Everyone who works in funeral parlours has the wildest sense of humour. Almost like they give you an aptitude test for the macabre as part of the training process. It was unsettling sometimes. But I had to admit, he had a fantastic singing voice. Couple that with the fact that the acoustics are always great in the places where our dead frequent, and I found myself thinking I’d probably listen to this guy’s cover album.

A lively breeze greeted me as I stepped outside, coaxing me to zip up my coat. It was early spring, so the detritus of melted winter still littered the parking lot. A thick layer of dusty grime lay upon the pavement, making the outside world seem more a tomb than the polished interior of the funeral parlour I’d just left. On the way back to my car I idly kicked at a crumpled Red Bull can, musing at the unfortunate mind-state a person must have been in to chug an energy drink before a memorial service. I’m always preoccupied with thoughts of other people. My therapist told me that it’s a coping mechanism so I don’t have to focus on myself. She isn’t my therapist anymore.

I got behind the wheel of my old Chevy Lumina and pretended not to be bothered by the growing rust spot along the base of the driver-side door. My mind was already several blocks away, at my next job. It used to make me feel bad, forgetting the deceased so promptly after I left them, before they’d even been buried or stuffed into the incinerator. But what use was it to dwell on them? Their mark on this world was transient, all but for this last ditch effort to leave an impact on me. It wasn’t fair to myself to try to shoulder that burden, day after day, usually for the sake of some guy who wouldn’t have spared me a cup of piss if they’d come across me ablaze in the street.

So as the funeral parlour diminished in my rearview mirror, so too did the last lingering psychic remnants of that poor soul whose crowning achievement was completionist run of Skyrim that took him under one hundred hours. And I felt no guilt as I let that ghost die. Don’t take your work home with you, the wise among us often say. Though if I’m being honest with myself, that is not actually a piece of wisdom I adhere to. I take my work home with me all the time. My work is all I’ve got.

God damn. Red light. I hated getting stuck at this intersection. The liquor store is right there. There is a line-up of people spilling out of the front door, all waiting to present their ID to a security guard before being let in. It was a particularly sorry crop of folks waiting to get their “noon on a Wednesday” booze. Mostly scrubby dude-bros, but also one woman whose harried look could largely be explained by the colicky infant strapped into the baby carrier on her chest. It was a sad sight, but it didn’t make the compulsion any less.

I had my one hundred day chip though, and I wasn’t going to give it up without a fight.

Green light. I released the breath that I didn’t realize I’d been holding. I resisted the urge to put the pedal to the metal, and drove away at what I like to think was a calm, measured pace. Much like the ghosts of the dead, the voices of the liquor store phantoms quieted with the physical space I put between us. It’s kind of wild how much beating addiction is just out of sight, out of mind. How if you keep moving forward those insidious suggestions of your own lizard brain have trouble keeping up with you. Sure, you’re bound to get stuck at a red light every once in a while. You’ll see the ghosts creeping up in the side mirror, even closer than they appear. The hardest part is waiting out the red. Sometimes you’re left wondering if green lights aren’t some Fairytale. But it will change back. It always does. You just have to remember that.

The urge to drink had mostly faded by the time I parked my car at the funeral parlour which would be my next jobsite. It’s funny. I keep telling myself that I could probably have the occasional beer if I wanted to. That it was the high stress of my old gig as a private investigator that drove me to overindulge, and that my life was at a healthier equilibrium now. I didn’t really think of myself as the kind of guy who would stay completely dry, and I felt like in recovery I’d learned pretty well how to have a better relationship with the sauce. In fact, could I ever rightly say that I was a newer and stronger me without demonstrating my control to have a drink or two without letting it get out of hand?

Yet I still recoiled at the thought of even having a single sip, as if in some deep recess of my brain, I knew better. It’s weird, isn’t it? That one part of the unconscious brain can be directing us away from the primal urges of another part of the unconscious brain. Meanwhile our conscious awareness is stuck in some fantasy of cohesion, utterly divorced from the conflicted reality of our biology.

Distracted as I was, it was hardly a surprise when I tried to step through the front door of the establishment only to crash into it with enough force that my nose smooshed against the glass. It was a pull door, not a push. I’d been here for nearly a dozen services, and I still did it every time.

Maybe spend less time thinking about brains and more time using yours.

“Right enough,” I agreed with myself aloud as I pulled the door open, resisting the urge to rub at my sore nose. Thankfully I didn’t think anyone had seen me.

Not that there were any people here to witness my moving about the world as if lobotomized. The foyer inside the entryway was entirely deserted. The thick grey carpet which allowed one to walk about silently, as if upon a cloud, carried nary a single dusty tread mark upon it. Nobody had been through here. And considering the service was set to start in just a couple minutes, it didn’t seem likely anyone would be. I could walk into all the doors I wanted. A number that was apparently legion, if my actions were an accurate barometer.

Ultimately I decided one door was enough for today and made my way into the next room. Here was the lobby, where a small reception area had been set up optimistically, on the off chance that perhaps some unexpected mourners would arrive. But not too optimistically. It only consisted of a single small table tucked off to the side, upon which an unopened bottle of apple juice sat next to an unopened sleeve of plastic cups. Oh, and a red box of soda crackers, also still uncracked. There were a few chairs, but nobody had bothered to unstack them.

I was not unaccustomed to empty funeral parlours, but I don’t think I’ll ever shake the uneasiness they stir in me. The rooms are often designed to dampen sound, so the silence hangs thick. And in it I imagine I can almost hear voices. Not the ghosts of those dead who have passed through this place, but those of the living who aren’t here. The faint hopes of the corpse still lingering before following the rest of the spirit into the next realm, ethereal projected imaginings that just maybe somebody will come to grieve them.

If that’s what they were, then the guy in the casket in the next room was fooling himself.

I left the lobby behind and entered the predictably vacant casket viewing area. The dulcet tones of a church organ buzzed on the air, though they were of the canned variety, playing off a small Bluetooth speaker in the corner. There was only a single chair put out in the audience. For my expected attendance, I knew. The undertaker stood at a podium next to the casket, wearing a dark turtleneck and slacks like he was Steve Jobs about to unveil the next iPhone.

Or the next die Phone, I could easily imagine the undertaker at my last job quipping. But the man at the podium would never make that kind of joke. This guy was all business. Always gave it his all, as if laying to rest the Queen of England in front of the entire Commonwealth in tears. Not to say he didn’t still make the dark jokes, but they were always after the service and in hushed tones, like a creepy little secret. I never stuck around long after his services because honestly, he kind of spooked me.

“Welcome, Samuel,” the undertaker said solemnly. I’d only ever introduced myself as Sam, but he always called my Samuel during the service, like we were acting out a Bible scene. “Please find your seat. We are about to begin.”

I nodded and sat down.

“Friends,” the undertaker began. “We are gathered here today, to honour the passing of Matthew Klammer. A life cut short too soon, yet he undeniably left his mark with the time he had. He will be missed by many.”

A pile of bullshit if there ever was one. I’d done my homework on ole Mattie there, lying there with a serene looking on his blushed up face that I doubted had even known such peace in life. I always did a deep dive on all my jobs before showing up. I might have left being a private eye behind, but some habits die hard, you know? And I’ve got to say, these folks that the State pays me to mourn at their funerals, they’re some fascinating people. Their stories are always wildly different, yet always kind of the same. It’s not like being a private eye either, where digging into the life of a cheating spouse or a crooked cop can land you into a heap of trouble. No, the dead don’t really give you any of that hassle, especially the ones who die alone. So you can dig into their lives to your heart’s content.

Not that I usually have to do too much digging. Most of the time these guys practically leave a detailed daily diary on their social media, wide open for anyone who cares to come looking. Take Matthew up there in the casket for example. Or Mattie, as he was known to his little circle of Bitcoin buddies on Facebook.

I wasn’t sure if anybody in real life referred to him as such. Near as I could tell he didn’t have much in the way of personal relations IRL, as the kids say. His wife had stopped talking to him after he’d “invested” their life savings into a novelty cryptocurrency which had crashed faster than a Tesla on autopilot mode. His daughter had stopped talking to him shortly after she’d come out as transgender. Mattie had taken this revelation about his daughter as an opportunity to regale her with his grade-school knowledge of biology, his passion on the topic belying the fact that he didn’t have the slightest idea what he was talking about.

Not that this was how he spoke of these events in his own postings. In his own words, he was the victim of a vindictive wife who didn’t understand how markets fluctuate, and a daughter who had been brainwashed by the postmodern Marxists teaching at her university. And his self-pitying posts about it always received tons of support and confirmation from people who he would never know more intimately than their tiny thumbnail profile pictures next to little blocks of text.

But going through the trash outside his rundown apartment, I’d seen the credit card statements and how he’d been living entirely off cheap frozen dinners. The market was not going to fluctuate him out of this hole. And I’d seen his daughter’s tearful Tiktok videos telling her side of the story. Her words chilled me as I recalled them, looking up at the empty vessel which had once been her father.

“Maybe the worst part is,” she sniffed as she wiped away a mascara-laced tear. “I would forgive him if I could just have my old Dad back. But it’s like he cares about what those losers on Reddit think of him more than me. I don’t even know if my old Dad is in there anymore.”

She certainly right now, but she’d probably been right back then too. He’d gone on posting his angry screeds to the same little audience of cheerleaders right up until the day he hung himself. Six days he’d dangled there in his apartment until finally he’d stunk enough that the building’s caretaker had come in and found him. My contact at the police station told me that his poor cat had already eaten some of the meat off his legs and had to be put down. Nobody at his work at the auto plant had even noticed him missing. I’d gone down there to ask around about him, and the best I got was a couple coworkers who recognized my description of him well enough to say they were on a “hey buddy” basis.

“—never shied away from an honest day’s work,” the undertaker was saying when I tuned back in. “And tragically, perhaps nobly, in the end he gave more to this world than he got out of it.”

The undertaker’s heavy make-up job didn’t entirely conceal the rot in Mattie’s face, but at least his flowery words covered the rot that had present in Mattie’s soul long before. I looked around at the empty room. I knew from my research this morning that nobody on his social media had questioned Mattie’s absence with any more alarm than an offhand “haven’t seen Mattie in a while.” It was nearly two weeks since he’d last posted.

After the undertaker finished, I wiped a forearm across my moistened eyes and turned for the exit. I offered a mumbled “bye” as I fled. My battery for the day was completely drained, and the last thing I wanted to do was get stuck in a conversation with this guy. I knew he would assume I’d just been deeply moved by his puff piece of a eulogy.

“See you soon,” the undertaker called after me. “Real soon.”

The bastard didn’t even offer a chuckle to show he was joking. I didn’t turn back, because I feared seeing the sinister smile I imagined must be stretched across his face as he watched me depart. Joke or not, I decided I wasn’t going to accept any more jobs at this parlour unless money got real tight.

After a couple more jobs and running some errands, I settled down at home that night with a big glass of iced tea to watch the nightly news. I never touched the video games, and the only time I went on social media was to do research for work. I’d just seen too many lives destroyed by those poisons. It baffled me how anyone could lose themselves to digital toxins so fully.

I clicked the on the TV and started scrolling through the news channels.

“…the doomsday clock gets two minutes closer as nuclear war looms…”

“…another massive Arctic ice shelf collapsed yesterday, and global warming continues to…”

“For just $699.99 this designer blender will solve all your problems!”

“…growing income inequality blamed as violent protests erupt all over the…”

“…the stock market reached another record high today, leaving economists baffled as to…”

I clicked the TV off and rubbed at the budding migraine behind my eyes. Red lights flashed inside my head. Red lights without end, demanding a stop to the forward motion of time itself. What was left to do but obey the traffic laws? But waiting on the world to change…well, it’s thirsty work.

Alex Passey is the author of the novel's Mirror's Edge and Shadow of the Desert Sun. His short fiction, poetry and journalism have been featured in many publications, most recently in the graphic novel Twilight of Echelon, the Apocalypse anthology from Dragon Soul Press, and the Winnipeg Free Press.

‘Lillian Singer’

Erich von Neff is a San Francisco longshoreman. He received his master’s degree in philosophy from San Francisco State University. He is well known in both French avant-garde and mainstream literary circles. In France, he has won awards such as Prix 26, given readings at the Cafe Montmartre, and published over 1295 poems and 289 short stories. In 2023, Editions Unicite published his book, 6 Affaires rèsolues par Frieda et Gitta: notre duo de charme de la police parisienne.

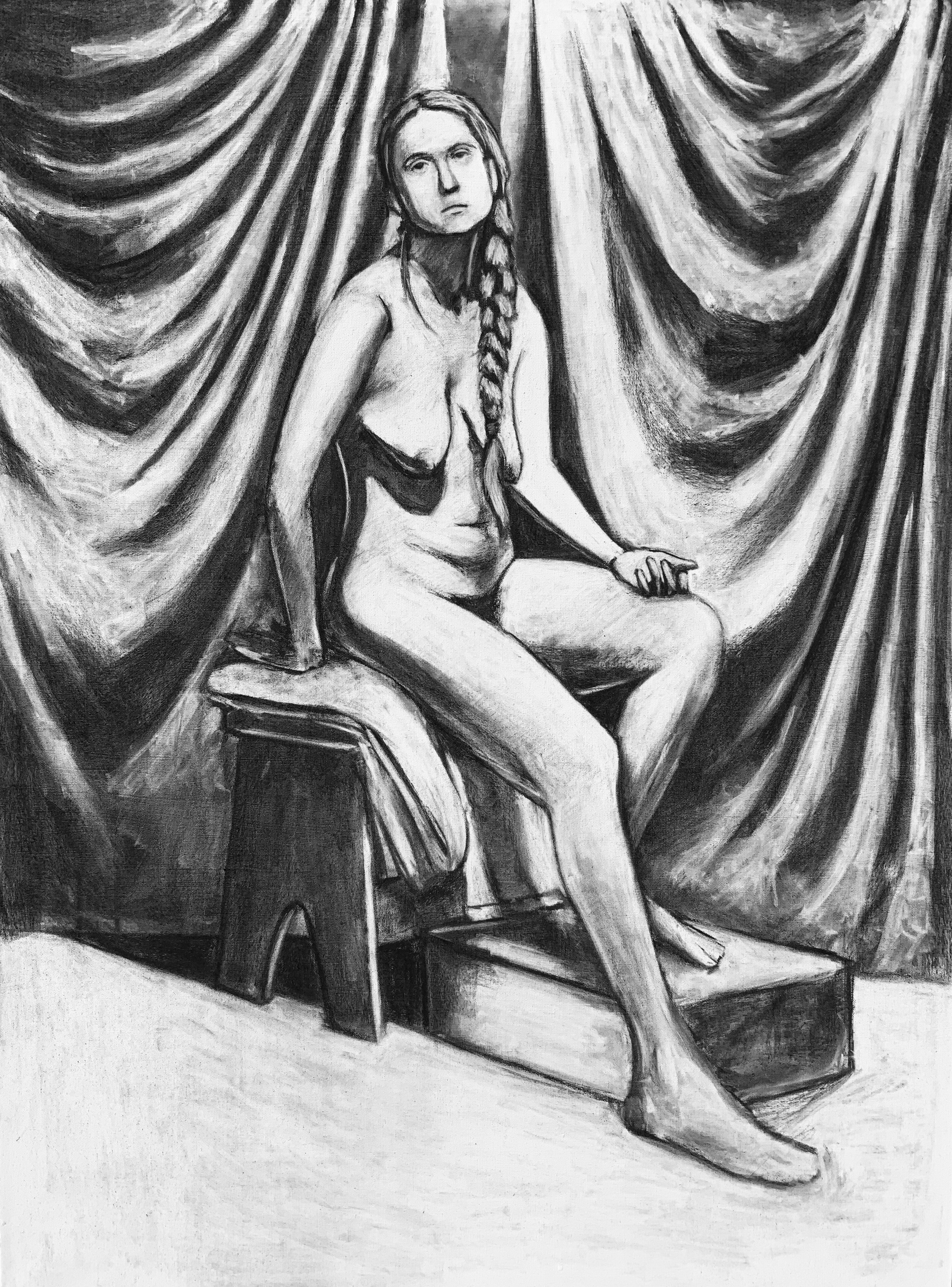

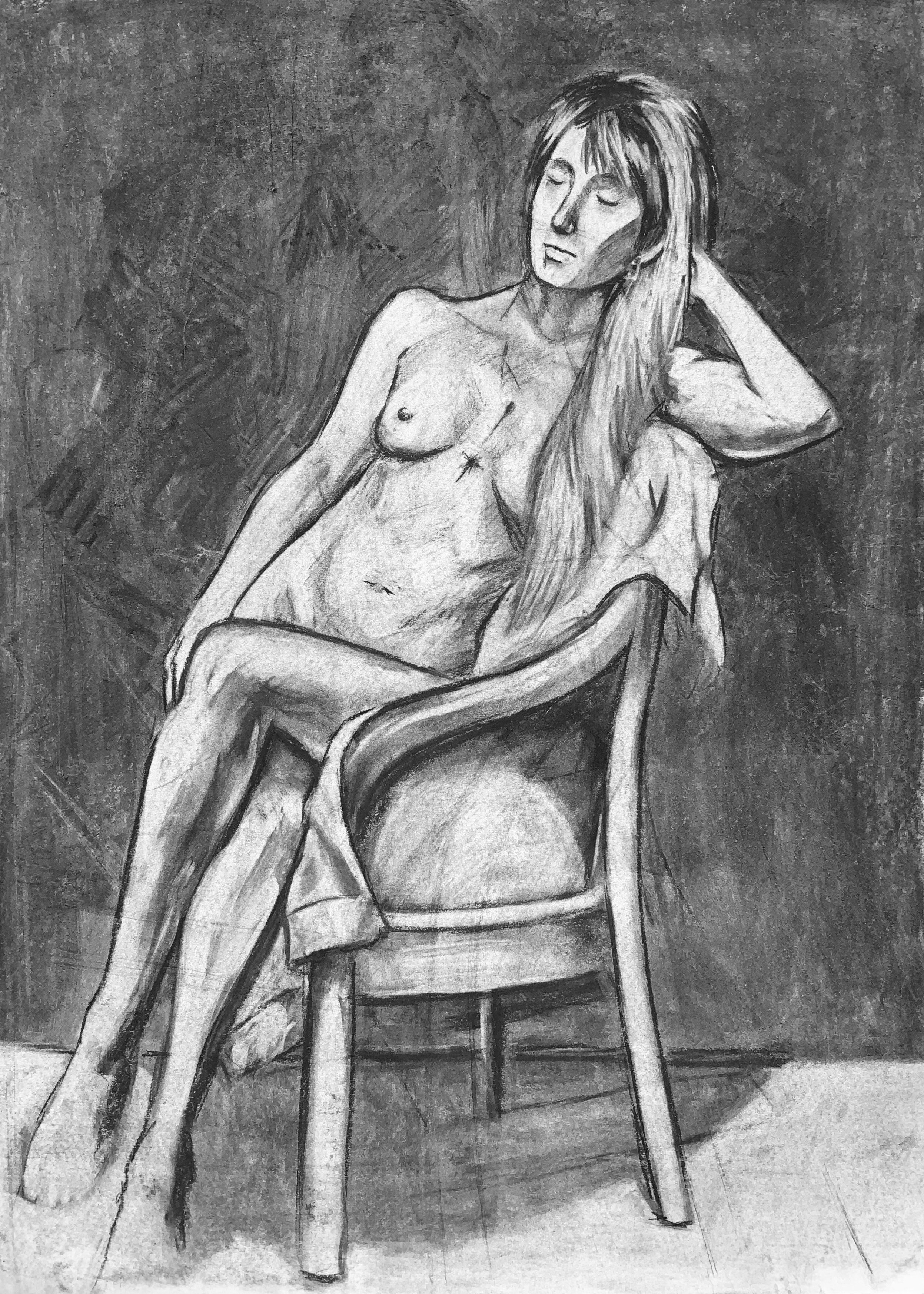

David Summerfield’s photo art has appeared in numerous literary magazines/journals/and reviews. He’s also been editor, columnist, and contributor to various publications within his home state of West Virginia. He is a graduate of Frostburg State University, Maryland, and a veteran of the Iraq war. View his work at davidsummerfieldcreates.com

Lillian Singer

Clement Street, San Francisco, 1968

I have long been convinced that the Staszow Ghetto* lives on -- perhaps in rudimentary form -- at the northwest corner of Seventh Avenue and Clement Street in San Francisco.

It is here that Lillian Singer brings her shopping cart filled with old books, dolls, clothing, and other items she has collected. Dressed in her babushka and frayed coat she sells her wares which amazingly people buy, though she never completely sells out. Some books and a few items are usually left over at the end of the day.

It should be remarked that Lillian Singer remembers little of the Staszow Ghetto which her family left in 1938 for New York, then San Francisco. Perhaps pessimists have better survival instincts or are just more realistic.

Since Lillian Singer lives near where I work, I have on more occasions than I wish to enumerate, driven her to Seventh Avenue and Clement Street. She seems to wait at the bus stop just about the time I get off from work. She stands there waiting patiently, her shopping cart filled with sundries.

Need I say that fellow employees have criticized me for “getting involved.” Perhaps this is because Lillian Singer does not have blonde hair, blue eyes, and is not long legged. A more acceptable choice to drive somewhere.

Nonetheless I have driven Lillian Singer to “her corner” at Seventh Avenue and Clement Street. I’m not sure how she manages on the bus. The top layer of her cart is indiscriminately placed and Lillian Singer has a tendency to spill. Also she often has a shopping bag full of other additional items.

I have to admit that I am always somewhat annoyed at the way I have to jostle the cart around to get it fit in the back of my car. It seems to have a mind of its own. Sometimes it fits in sideways. At other times, it fits straight in or on its side. This is because I am always trying to maneuver it so that the least number of items fall out. Books and clothing spill anyway. So why do I bother? Yet it really does seem that one position would be less disastrous than another, for Lillian Singer never packs her cart the same. Items are always to one side or another. The weight is not evenly distributed.

Lillian Singer gets in the car and says something like, “For me you shouldn’t have done this.” Yet I have; and she has accepted the ride nonetheless.

Lillian Singer has a tendency to talk about her sister and her mother. Her sister teaches school and the kids don’t pay any attention.

“Kids these days, I’m telling you.” Her mother lives with her sister and they don’t get along. Her sister charges her mother too much rent.”

“For such a mother she should be grateful.” And on.

“She shouldn’t charge her any rent. Besides an old woman on social security shouldn’t have to pay rent.”

I couldn’t but agree with that.

“For such a mother,” who foresaw it all. Who demanded that papa bring the family to New York from the Staszow Ghetto when Lillian Singer was still in kindergarten.

In the Staszow Ghetto papa had worked as a kosher butcher, but in San Francisco he worked among Germans, and Italians in San Francisco’s Butchertown. Breaking up hogs, steers and even horses.

“What papa wouldn’t do to survive.”

“For the kids. For mamma.”

Papa had died young. At thirty five.

“He shouldn’t have worked in the slaughterhouse.”

“But what other trade did papa know?”

Mamma got a job as a buyer for Grodin’s Clothing Center in the apparel market. Without a complaint she worked sixty hours a week, putting the kids through school. Finally Lillian and her sister graduated from San Francisco State College** when it was on Laguana Street.

Their paths ran parallel for a while, both teaching primary school, then they went their separate ways.

Lillian Singer began holding garage sales.

“For this mama worked? For this papa died?”

Lillian Singer moved to a room in the basement. She began selling here and there in the City, finally fixing on Seventh Avenue and Clement Street.

I’ve never asked her why. But there’s a lot of foot traffic, obviously reason enough.

Lillian Singer has given me a poetry book, e. e. cummings, 50 collected poems.

“There was no buyer for it today.” Surely there might be one tomorrow or the next day.

“You are a poet. You need this.”

I took the book.

Again, I have given her a ride. I have picked Lillian Singer up at Thirty-Sixth Avenue and Judah Streets, muscled in her cart with accouterments: lopsided with books and dolls hanging out.

“For this mama worked. For this papa died?”

Lillian Singer climbed in next to me.

“Will people buy these?”

Lillian Singer doesn’t know yet. She always seems to sell what is on hand, though not as much as she’d like.

Then, too, there is her work registering voters for the Democratic Party. She sits in front of a card table, wearing a straw hat with “Democrat” pinned on it. She’s paid by the number of signatures she gets. This “booth” is also at Seventh Avenue and Clement Street. She has rapport with the neighborhood.

I stopped at Seventh Avenue and Clement Street. I pulled out the cart while Lillian Singer steadied the dolls with her small boned hands. She pushed the cart over to the Athletic Shoe Shop and began to set up shop. Which consisted of spreading newspapers on the sidewalk and folding the clothes in neat piles on top of them. She put the dolls on the clothes, their backs leaning against the orange tiles of The Athletic Shoe Shop. They were the right height for children to see. One was a Raggedy Ann Doll. She had a big smile.

People walked by. Lillian Singer smiled her wistful smile. A woman in a business suite browsed, thumbing through a few books. She bought Danielle Steel’s “Season of Passion” novel for a quarter. The dolls and doll clothes remained. Would they sell?

For such a mother. For such a father.

From the Staszow Ghetto.

Now located at Seventh Avenue and Clement Street. Where Lillian Singer sells books and dolls.

Already there was a little girl looking at the dolls.

From the Staszow Ghetto -- in rudimentary form -- they smile. They wait at Seventh Avenue and Clement Street. -- The Staszow Ghetto Annex. Where Betsy Yang sells shoes at the Athletic Shoe Shop. Where Max the saxophone player across the street plays “Misty.” Where Bear the Lakota Indian drinks Midnight Express.

They wait. For such a mother. For such a father.

---

* Prior to the Holocaust Period the part(s) of a city where Jews congregated were called shtetl, though they are now popularly called ghettos. Officially, the Nazis established the Staszow Ghetto in June 1942.

** Now San Francisco State University.

Erich von Neff is a San Francisco longshoreman. He received his master’s degree in philosophy from San Francisco State University. He is well known in both French avant-garde and mainstream literary circles. In France, he has won awards such as Prix 26, given readings at the Cafe Montmartre, and published over 1295 poems and 289 short stories. In 2023, Editions Unicite published his book, 6 Affaires rèsolues par Frieda et Gitta: notre duo de charme de la police parisienne.

‘The Armory’, ‘Buttercup and the Afterlife’ & ‘ At the Pinnacle’

Alan Hill has been writing like his life depends on it; because it does. He cannot imagine there is a better way of trying to make sense of the world that follows him around with its bad breath and big hairy fists. His latest book 'In the Blood' was published by Caitlin Press in 2022.

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldlpatten.newgrounds.com/art

The Armoury

I can see it, her love for me

has dampened my fear, its

broad fingered prairie blaze

cauterised the

dissolution, disease, the death

that will come at me now

that little harder, with its fists raised

swinging its fat little arms

now that I have something

somebody to lose

I have something it wants.

I will step into the arc of her

the mountain austerity of

who we are, to make myself

a target, ready for the punch

open to the strength of us

to the soft machinery of us

small fishlike bones of how we fit

in how we bloom with the

seriousness of the sky

with the ritual within our bodies

which must be carried out, the

soft muck of her and I exposed

aligned, spread like weapons

on a blanket.

Buttercup and the Afterlife

In rain I am walked by the dog

herded by her darkened muscle over

potholed streets

compelled by the froth of wolf cub

love beast

edgeless unnavigated coagulate of

lightness track

expanse of back alleys, cut throughs,

desire lines

navigated by snout, netted in a

flush of scent of

consummate gutter sniffer, fur bound

trash hound

into sightlessness, the slip of the knot

of being

to move out across curb ways into

the patterns

of the elderly, morse of post divorce

death wait, freedom beyond the

human of me

into the

swarming approach a of silence, a

winter evening, off the leash.

I am a dark wing; the sky is a bridge of

birds, indistinguishable, one.

Father, Mother, take me home

It is time to go, be never heard of

again.

At the Pinnacle

I have spent time with it

this stink, naked wheeze of

all I have not lived

sat with it in the dark

held hands with its boneless

featureless form

pressed my teeth into the

hard bread of soured love

known it as mine.

Not that I care.

When I was ten, I

reached those plumbs

slithered myself over the

plastic sheets

of the shed roof

the one

shoddily built by my dad

I was told to stay away from

that could collapse at any point

impale me on his hoard

on unused garden tools

to seize the fruit

the perpetual flowing ocean of

sugared love, the dead eyes of

an unjudging god

want free isolation of the

highest branch.

Alan Hill has been writing like his life depends on it; because it does. He cannot imagine there is a better way of trying to make sense of the world that follows him around with its bad breath and big hairy fists. His latest book 'In the Blood' was published by Caitlin Press in 2022.

‘Right Here, Right Now In My Childhood Home’, ‘The Stranger at the Record Store’ & ‘The Basement’

Julia Frederick is currently an undergraduate student at the Pennsylvania State University studying English. In her free time, she enjoys listening to music, growing her record collection, and writing poetry and creative nonfiction. Her work appears in Ink Nest Literary Magazine and Folio (a chapbook edition of Penn State's Undergraduate Literary Magazine). She has two pieces forthcoming in BarBar.

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldlpatten.newgrounds.com/art

Right here, right now in my childhood home

“God’s in His heaven— All is right with the world.”

- “Pippa Passes,” Robert Browning

Can I stay right here, right now, forever?

Layered under blankets, my sister twitches in her sleep.

I stare up at the ceiling, peer through my childhood years and rest for a moment. For now, the world stops its crazed rotation. For now, everything is perfect.

Beneath pink princess blankets, my sister twitches in her sleep. She dreams despite Dad’s snores ricocheting on cement walls. For now, the world pauses its crazy routine. For now, everything is perfect. I’m afraid of the day space heaters and CDs and Disney movies fade.

My little sister dreams in spite of Dad’s snores ricocheting on cement walls. I stare up at the ceiling, clinging to my childhood years, resting for a moment. I’m afraid of the day this will change. When this too becomes a memory. Can I stay right here, right now, forever?

The Stranger at the Record Store

My sister and I walked along crimson carpeted aisles of records and CDs.

Their faces bearing peeling cardboard and coffee stains like scabs and bruises.

We met a man in worn Carhartt with tired grey eyes among the cassette tapes.

Together, we talked about our heroes:

the Starman,

Her Majesty,

the Fab Four.

He smiled, said our parents raised us right,

and we agreed.

And for a moment, years no longer

divided generations.

For a moment, the world wasn’t broken.

He left before us, paying the cashier with

a six pack of beer.

The bottles clinked in time with the bluegrass

on the turntable.

We left soon after, placing our finds on the counter. The cashier placed an extra vinyl on our pile

from the Carhartt man.

His favorite album from the seventies.

In the car we stared at it,

it’s been through the wringer

I thought but then realized no,

it is well-loved.

The Basement

Dad sits on a blue-cushioned stool, guitar in hand

Flips the pages of a songbook bearing waxy crayon scribbles that you were convinced were cursive

He built this house, penciled measurements on the walls and wired the electrical cords adorning the ceiling that he never got around to covering

With popcorn kernels and pretzel crumbs embedded in couch cushions, here is his breathing time capsule,

a testament to fifty years well-lived

He strums a few chords before pausing, asks you to join him

You know the words, so you gladly ignore the freezing cement floor beneath your bare feet

Together you sing

And it is as beautiful as a father singing with his daughter

When you grow, Dad says the place looks junky

That the McCartney tickets and newspaper clippings

hang haphazardly; a mess that needs to be cleaned up

You wonder how he could say that

about the place that raised you

Your guitar now rests in a stand in the corner next to the others

Leaving your fingers calloused, stained gray, smelling of metal

Just like his

Julia Frederick is currently an undergraduate student at the Pennsylvania State University studying English. In her free time, she enjoys listening to music, growing her record collection, and writing poetry and creative nonfiction. Her work appears in Ink Nest Literary Magazine and Folio (a chapbook edition of Penn State's Undergraduate Literary Magazine). She has two pieces forthcoming in BarBar.

‘Holly Blood Stains Our Palms’, ‘Down the Drain’, ‘The Night Sky Is A Grave’ & ‘The Crane and The Flower’

Quinn Marley Garcia is a writer and part-time cowboy. She was the first youth playwright to have a piece virtually performed at the Little Fish Theater in LA, and has been published in multiple literary magazines.

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldlpatten.newgrounds.com/art

holly blood stains our palms

speak to me of dollhouse days from the theater of your mind.

conversation blooms and beads like blood from our lips

and our hands, pressed and split with letter openers and holly thorns to reveal

the sweet and tender fruits of our fate lines-

addressed to each other, we read off recountings:

you, the past, and

i, the future.

we speak and manage through

the slow drip of death, the muddles of bygones,

and whisper poetry composed for ourselves from the rawest fibers our lips can spin-

frequently, we lose the plot, and the blood that traces our palms flows

quicker to the earth;

the bitter juice of the holly berry,

the insides of our minds and our hands come to

drip and drop between us,

to color the earth red long after we are gone.

what sort of abstract art is this, what meaning does it have but to bind us?

when we press our bleeding palms together

and seal our brief exchange with an oath:

“shake on it my good man,

promise it won’t be easily forgotten,

the blood we’ve spilt here today.”

i hope the sweet and bitter aftertaste of memory, like berry juice

will taint your tongue and stain your hand,

so you can recall our agreement

when our conversations are mere scars on the palm.

and though in retrospect, you may think the taste too bitter, or the marks too plain and faded,

i pray you will know that i look upon the scars as words

or fate lines,

dissecting fond meanings in each sweet phrase we spilled.

Down the Drain

I cried in the shower

over the

preemptive loss of time.

My tears swirled blissfully

down to oblivion

and when I was done

It seemed as though

my sadness

had never existed at all.

The Night Sky is a Grave

She’s on the lawn, irreparable, watching the moon slide down her cheeks like tears, awake at an unholy hour, inside her family grieves, inside she is part of a whole, a mourning mass, made unspecial in her sorrow, out here, under the falling stars, she is singular in the night sky like a cold and dark planet or an exploding celestial body, out here, she is her own ever-expanding, ever-weeping universe.

She sits on the lawn, and she cries.

The Crane and The Flower

you sat down at the table

and looked at the potential until you saw me

in the blank and the paper cuts.

like the tender mother shapes the child, you took my corners

and folded them into wings.

when you kissed my forehead i learned to soar-

you have given me the gift of flight.

your own rustling hands were themselves still semi-formed,

for you had hardly bloomed yourself, with

paper petals so raw and new that

it seemed unfair to burden them with another life-

yet you cradled me still,

took me on willingly:

the greatest sacrifice a person has made for me.

and now you are carried,

a paper flower on a western breeze,

spinning and circling back to me.

yet if you did not return,

if your days weighed you down or your petals grew too thin-

then the wings you gifted me will always

blow me back to your waiting smile;

the little paper crane forever drawn back to

the fingers of its creator.

Quinn Marley Garcia is a writer and part-time cowboy. She was the first youth playwright to have a piece virtually performed at the Little Fish Theater in LA, and has been published in multiple literary magazines.

‘Fragmented’

Chloe Kultgen graduated from Minnesota State University, Mankato with a BFA in Creative Writing. When she’s not reminiscing on the past or speculating about the future, she enjoys spending time by Lake Michigan looking for hidden treasures that wash ashore.

Donald Patten is an artist and cartoonist from Belfast, Maine. He produces oil paintings, illustrations, ceramic pieces and graphic novels. His art has been exhibited in galleries across Maine. His online portfolio is donaldlpatten.newgrounds.com/art

Fragmented

I think there was a fear of self

that had found a home

within my bones

as a child, I had been left with

discarded pieces of safety

& forced to imagine what

unconditional love felt like

stranded

& made to scratch away

at my skin—

a desperate attempt to

understand why I deserved neglect

& question what was wrong with me

thought that if I searched within

& dissected myself enough

I would uncover what needed to be changed

yet the more I looked, the more I started to hate, the more I started to compare, the more I started to question, the more parts of myself became

s h a t t e r e d

by

m y

o wn

h an ds

until

I had

been

left

with

nothing—

my

identity

fragmented

but as I have been attempting to

figure out who I am now

&

constructing my foundation of needs

I have discovered that

home is a hug of self love

that will never let you go

&

home is about finding

the pieces of yourself

that you abandoned long ago

&

finally allowing them

a safe space to live within your bones

Chloe Kultgen graduated from Minnesota State University, Mankato with a BFA in Creative Writing. When she’s not reminiscing on the past or speculating about the future, she enjoys spending time by Lake Michigan looking for hidden treasures that wash ashore.

‘Tender’

Jovi Aviles is a teen writer whose work has appeared in The Malu Zine, PWN Teen, and Pen&Quill. Her favorite authors are Madelaine Lucas and Sylvia Plath. She is often found at her favorite cafe writing.

David Summerfield’s photo art has appeared in numerous literary magazines/journals/and reviews. He’s also been editor, columnist, and contributor to various publications within his home state of West Virginia. He is a graduate of Frostburg State University, Maryland, and a veteran of the Iraq war. View his work at davidsummerfieldcreates.com

Tender

The first time I saw my father cry was at confession. While I didn’t know what it was then, I remember sliding between the pews in my puffer coat, pretending I was a goat sliding down hills of marshmallow. I remember tracing the art sculptures in the Vatican with my index finger, pretending the crying angels were princesses welcoming me home.

When his divorce from my mother was fresh he fell out of that faith he used to preach to me before bed, mumbling quiet prayers into the shy tunnels of my ears. On those quiet nights–when snow was busy swirling and sticking slick to the windows of our empty house, the one being rescinded and collected back from the bank–he would tuck me in up to my chin. I would never tell him he was doing it wrong, even though the whiskey-stained sheets would scratch against my flesh like a pinecone and the chill from my window panes would reach the tips of my toes. Sending a shudder I’ve only ever felt on those lonesome nights, when I could almost feel my fathers faith slipping like cloudy bath water.

Sometimes, as he pulled me from the tub and wiped my hair and my face dry with damp towels, I saw faces in the water. Little clouds of ghosts swirling into the drain, whispering something indescribable. A secret swapped between bubbles. Later, I would believe that image to be the white holiness of my fathers religion sinking into the drain, leaking back into the ocean where hopelessness was a common ancestor in a sea of dreams left dead and bone-dry.

In the mornings with my father, I always woke up to the smell of pancakes. There would be batter smeared on the countertops and orange juice propped on the table ready for me to pour. I would pick out the splinters in my highchair that stuck my bare toes, while waiting for the pancakes to flip on my plate because while we couldn’t afford socks that winter, we could always afford batter and blueberries.

As if we weren’t getting pummeled to death with the weight of the world already crumbling on our tattered shoulders, this condemned God sends sickness to my fathers younger offspring.

My socks had all gone to my baby brother who was still at my mothers, getting nursed back to health after pneumonia ravaged him like starved, barbarian racoons. My mother attainted to him like a personal nurse, and sometimes I watched her nursing a few times that winter when my dad would drop me at her doorstep and wheel away in his cherry red convertible.

She would bundle up every inch of his skin in socks, these big, fluffy socks that were stained with my scraps of food and blood from my routine splinters. Then, she would take the big lard of fat that was my brother into her chest, warm him like he had been sitting out in the North for days while the wind whips his cheeks raw and red. I asked her to do that to me, once. To feel a touch other than my fathers calloused, construction hands. To feel the essence of my baby brother’s lotioned tummy, his lotioned face and feet. Maybe even to hear my mother’s heartbeat, hear Jesus whispering and confessing his identity to me. Maybe that would’ve made me reserve my Sunday mornings when I became a young, red-heeled woman.

“Can’t you be like that with me, mama?” I pleaded. She looked up from his face then, let him continue suckling what was left of her inside her aged, wrinkled breasts. “He needs tender.” She whistled through clenched teeth. Grizzly. “You had that tender before. You don’t need more.” She said, plainly. She looked through me like I was a hologram, like I was an aloof daughter mistakenly placed in the wrong house. A mute daughter who expresses feelings through her fingers, her wrists, her eyes.

And I did when my father buckled me in on Sundays. For months on end, those chilled, frigid months, we survived solely on the circle bread they would feed us between hymns. He

would get to drink the juice that smelled like roses and coins. I wasn’t old enough, or maybe I wasn’t holy enough. I never heard the priest right. I don’t think I ever heard him right until his old battered hands went up my skirt after my first confession, and he dangled his twisted fingers into a crevice I was told was too valuable to let another man destroy. But he justified it with the word of God, forgave me of all of my sins that had been littering my mind.

I walked out of that thin box fixing my skirt and wiping the blood from between my legs. My father was waiting for me by the great big doors, shook hands with the priest, an evil grin plastered on that wrinkly face, and led me to his car that was blanketed in iced snow. “Daddy?” I croaked on the way home.

“Yes?” he muffled through his mustache.

“Do God’s people commit sins?”

“Sometimes.” His eyes were locked on the road. We drove over frosted roadkill. “Are they forgiven?”

“They aren’t witnessed.” He cleared his throat. “They are pursued in silence.” I didn’t know what that meant as we traveled through dirt roads on flat tires. I merely felt the bump and potholes in the road a little stronger that night, I merely hurt a little more in the shower and on the toilet and under my sheets that still smelled of whiskey. I burned.

Jovi Aviles is a teen writer whose work has appeared in The Malu Zine, PWN Teen, and Pen&Quill. Her favorite authors are Madelaine Lucas and Sylvia Plath. She is often found at her favorite cafe writing.