THE EXHIBITION

•

THE EXHIBITION •

‘Vital stats’, ‘The Purloined Hearts Of Southern Command’, & ‘Not Joes’

Mark Kessinger was born in Huntington WV, attended college at Cleveland State University, lived in Oklahoma City and now resides in Houston TX. He is a two-year recipient of a creative writing scholarship from CSU, a founding member and president of the Houston Council of Writers, and former editor of Voices from Big Thicket. His poetry has appeared in many publications and four anthologies.

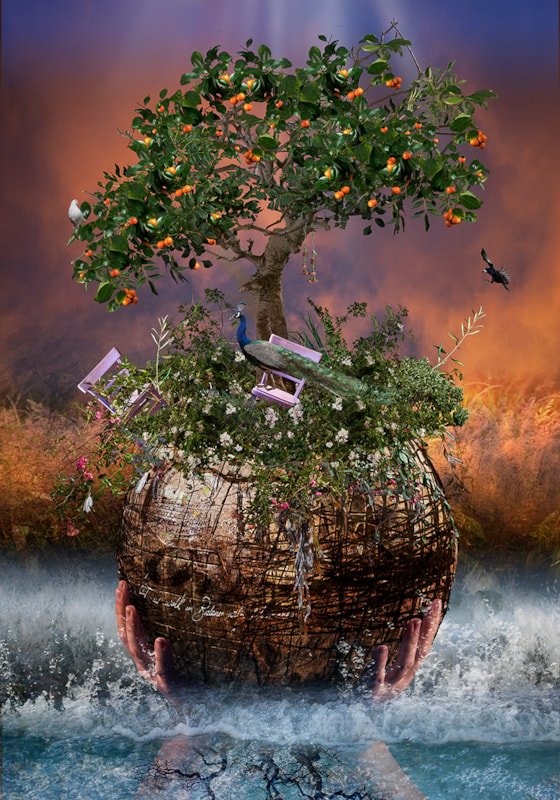

Artist - Christine Simpson, www.christinesimpsonphotoart.com

Vital stats

Perhaps in the next war

we can put every soldier's face

on a bubblegum card.

Force civilians to collect them,

thousands of new ones every day,

and issue update stickers

for all the wounded,

the missing in action,

all the dead, the deserted,

captured,

the executed.

I love stickers

as honors won,

medals given,

ribbons earned.

The public, (that is,

the non-combatant parts of the world),

may sicken of the fight

just a little quicker.

I suppress the idea

because it would really be perverted,

in true war, to where we would

only collect faces of the enemy.

waiting for 'our' official updated dead,

wounded, or captured stickers,

we would take the 'others'

to poke out their eyes with dart tips,

burn their faces with flame,

boil the disfigured cards to mush...

which we would use for magic spells

and prayers for death and plagues

and our teeth would rot out by the fistfuls

from the bile we poison ourselves on!

How easily war gets away from us.

The Purloined Hearts Of Southern Command

Ms Hometown Rose

was recruited by error.

She received the draft notice

via mistake of her

shortened surname.

An unnatural twist that

birthed empathy.

She sent her photo

to the first Joe

who showed it around.

Naturally.

She got other letters.

Naturally.

Her picture showed

a real honest to goodness goddess,

a stateside beauty queen with

girl next door give-a-damn.

She kept copies of her letters

from over three hundred Joe's

under her bed, in files, boxes,

on her side of the attic.

In time, they would all

come home, or die there.

In time, they would all forget.

Naturally.

Beauty queens get buried

with all the other memories of the war,

all the things real life sweethearts

and wives might not understand.

Her letters died in the fires

of a jealous ex-husband

who never served in war,

or, as she puts it,

just never served.

Not Joes

In a war with some name,

we, the not-Joe's, did not go.

Never went. Never knew.

It was a test given

and not taken,

graduation held but not

attended, an

initiation of fire

not felt.

Most of the generation

un burned

un scarred

un healing

marches on.

The sound of the missing drummer

flying the blank flag,

vacant colors,

without declaration

or distinction,

knowing what it is

to be left alive.

Burdened with virginal courage,

un expose guts,

un tried fortitude.

Lucky in the draft,

lucky in life,

we drink without the

grateful tastes

of the seasoned survivor.

Unworthy of the actual

survivor's guilt

denied to civilians,

we live our

non-veteran lives, and

most likely meet our fates

with non-valor.

Unless, we do our duty

to cherish, cradle, and

deliver on this peace dividend,

paid for by the dead,

and those who's duty

was not to die.

Mark Kessinger was born in Huntington WV, attended college at Cleveland State University, lived in Oklahoma City and now resides in Houston TX. He is a two-year recipient of a creative writing scholarship from CSU, a founding member and president of the Houston Council of Writers, and former editor of Voices from Big Thicket. His poetry has appeared in many publications and four anthologies.

‘Soma’

Artist - Christine Simpson, www.christinesimpsonphotoart.com

Soma

A rainbow of blocks with numbers increasing from left to right, top to bottom, stares back at me. The unreliable BMI scale. Some of the numbers I can’t read due to the shine of LED overhead lights streaking the laminated poster with a nasty glare. I peer at the digital number that looks up at my nostrils when I’m facing forward. Ninety-eight pounds. The pungent smell of new scrubs and sterilization eminent the air. I feel dirty; I always do in a hospital.

“Three less than last week.”

The nurse in scrubs -- baby blue, the kind regurgitated all over the walls of a gender reveal party -- stands less than half an arms length away. I’ve never seen her before. Her face is set with thin wrinkles, framed by wisps of straw hair. Her neck juts out like a bird; her weight is resting on one leg - the common nurse stance. She’s new here, but she’s not entirely new to nursing. I can tell.

She’s writing on a form too far from view to read. “Follow me, we are going to room two.”

The door is already ajar because of the doorstop, but she splays her arm over it, showing some form of ownership as I walk in. “The doctor will be in, in just a few.” Her left foot instinctively releases the brake, and I see her flip the metal tab with the room’s number outward so it’s perpendicular to the wall, to show I’m ready to be seen. The door slides shut almost ghost-like, until a light sound announces it clicking into lace.

...

The pamphlet I was given shows a black and white version of a forlorn, depressed teenager leaning against a wall, peering out a window. She’s awkward, uncomfortable. The title in a thin font questions “Eating Disorder? What You Should Know if Your Child Has One.” Wrong audience, I say aloud. They gave me the wrong one.

The pages stick together, making it hard to open, and the pamphlet slips from my grasp to the hardwood floor. While reaching for it, my hands stop mid-motion. I stare at my outstretched hand. I no longer shake anymore when I’m hungry - just one of a few bodily changes I’ve noticed. It’s like someone turned off the craving of sustenance in my body. It’s no longer needed, finally.

Upon retrieval, my mom walks in the room. Her fashion is a slightly wrinkled set of lilac scrubs.

“How was the doctor’s?”

“Good -- great.”

“Did you get the prescription for your hyperthyroidism?”

I have no such thing.

“Yep. I went to the pharmacy today.”

Another lie.

“Awesome.”

Her body eases into the recliner diagonal to the sofa I’m on. Clandestinely, I shift the pamphlet under my right thigh as my mom takes off her no-slip shoes. Her tradition is to rub her feet after each shift in the ICU. Like clockwork, a sigh releases from her open mouth as

her eyes close in solace.

“Domino's tonight?” Her eyes still closed.

“Well it is Friday, right?”

“Mhmm, I’ll call in ten.”

The tension in her forehead releases, as her fingers rub a knot out of place in the arch

of her foot. Another sigh enters the air.

I stare at her. A plastic claw holds her golden hair away from her face, in a nest at the crown of her head. Well-shaped eyebrows overscore her set of gray eyes, while a small nose slopes gently down her face for the big main event: pouty lips, still a youthful shade. She’s beautiful. It’s the only way I remember her. When I was younger, I would look at her features, wondering how I could will my masculine jaw and dark brown kinky hair to mirror her soft femininity. I was never picked on as a child because of my looks. I was too average for that. I was always tiny. Small breasts; nonexistent ass. I was never a woman in anyone’s eyes. No curves that drew the attention of an older man’s gaze. I never would be that kind of girl. Not like I ever wanted that, necessarily. I knew back then, I just wanted to be pretty. I wanted to evolve out of the boring image of my long-lost dad and into something, someone wanted to look at.

“What’s wrong, Emily?”

Even my name was dull. I break my daze. “What?”

“You looked angry or, I’m not sure, maybe disgusted with me.”

“Resting bitch face is a real burden.”

My mom’s beautiful eyebrows pinch together with concern, but not too much concern.

“I’m just thinking,” I say.

This time, it’s not a lie.

...

I was in a sophomore biology class when I first heard the word soma. Although it owned the same number of letters as the word body, it felt more delicate on the tongue. It gave the idea of four limbs to a central connector and a wobbly sphere for a head more grace than the word body did. Soma was scientific, but ethereal in a bewildering kind of way. I could have with my soma, but not my body. When I was hating my encasing, I always thought I was thinking of it as my body because nobody could hate a soma. Sometimes the word comes to mind, interrupting a thought, and I let the two syllables drip slowly from my mouth. So-ma.

“Did you tell your mom about these weekly visits?”

“Yeah, of course.”

She knows. She knows about the wrong condition too.

“Good. Your mom is a great friend to many of the girls in family medicine. No one would want to out you accidentally.”

Her silvery gray eyes are flat, without emotion. “You, uh, you wouldn’t talk to her about my eating disorder though, would you?”

Her eyes widen. “No, no dear. I would never go out of my way to speak about any patient’s health. I just meant, you know, if any of us were asking about the family.”

“Mmh...right.”

“Don’t mean to concern you about a thing!”

...

When you lose weight unexpectedly and unintentionally over time people usually have the same response -- to say nothing. They would rather talk to the person who is gaining weight; whose fat is hugging the waistline of their jeans that once fit them. They may not say it outright, but they will insinuate the need to lose a few pounds by asking them to a gym date. With me, no one has said anything about the 21 pounds-and-counting that I’ve lost. There is something more privileged about an eating disorder that reflects lost weight instead

of gained weight. Society says visible rib cages are prettier than the concave dips on upper arms and thighs as symptoms of cellulite. I feel proud about mine; about my ribs on view, that is. I stare at them in my bathroom mirror, tracing each one with a bony finger until I feel

content. My morning ritual.

“I haven’t seen you take your anti-thyroid meds lately.”

As the non-patient of a mom who doubles as a nurse, I’ve noticed her metaphorical habit of picking up the closest knife and gently digging it in suggestively, yet politely. There are no direct questions in this household. She’s not on nurse duty; there’s no need for that. “I take them every morning; before work.”

“Oh, I just thought maybe I’d see the script laying around your bathroom at some point.”

“Does this mean you’ve been going in my bathroom, looking around? I’m 22; I’m not a teenager anymore, you shouldn’t be going into my stuff or telling me what to do.”

“Hey - don’t start a fight with me! You’re the one who doesn’t clean the bathroom and puts the onus on me. If you were living on your own, like you were when you were at school, you wouldn’t get all these questions.”

My stare falters. An instinctive eye roll regards the floor.

“Jeez, even if I haven’t seen them, you sure are moody like you are taking them. Guess I shouldn’t question you.”

She leaves the room cold, or maybe it's just the now 90 pounds of me needing some outside warmth, even if it's someone’s personality.

...

I like making lists. I have lists of everything, such as the number of months I’ve gone without my period. It’s like I’m identifying as a gymnast or a competitive dancer. I’m bigger than myself because I can stop something most every other woman undergoes. There’s strength in that, I believe. It takes a lot of perseverance to love your body, as it does to fully hate it. For the longest time, I just prefered to preserve the latter feeling. Now, things are changing.

I recheck the door is locked. A used orange medicine bottle sits on the bathroom counter. Digging into my purse, I find the pharmacy store bag. Sugar pills, or essentially the same thing, according to my research. The best part is they look the same as anti-thyroid meds. The pills cascade into the cylindrical tube, the one that promises I’m taking the right ones. To the side of the bottle is a sticker I created, looking imperceptibly different from a prescription tag. I ring it around the bottle gently, giving it good pressure for good measure. Admiring my work, I take one pill and throw it back before sliding the lid closed, tossing the bottle haphazardly on the counter. It’s ready for anyone who wants to see it.

“Emily? Emily?”

The normalcy of those syllables in my ear wakes me up. The screen of my vision comes in fuzzy on the edges, but I’m present. Enough.

“Mmmh?”

“You’re sleeping again. What if Patrice saw you?”

Thumbing spit away from my mouth and pushing hair behind my ears I get myself together.

“I know; I know.”

“You’ve said that every day for the last two weeks. It’s time to figure your shit out,” my co-worker said, whispering only the vulgarity into the space that is my cubicle. She stares at me with worry. I can see this. I can tell she’s giving her pitying look; it’s the same as everyone else. Eyes slightly glossy, brows pulled together just a touch, and a thin frown just above the chin. Looking at her, I’m starting to comprehend my spacey presence. “Are you sleeping alright?”

“Yeah, I’m just...extra sleepy. You know? Maybe, I don’t know, maybe I’m just B-12 deficient.”

“That’s serious stuff. I hear bad shit can happen if you don’t take shots or vitamins... just, just make sure to tell your doctor.”

“Yes, I know. I really should.”

“Maybe you need something to eat for a little more energy? I have an energy bar. You want it?”

Loads of protein. Calories stacked on calories. Yet, she’s yearning -- begging me to take it.

“Okay, yeah, thank you.”

She hands the silvery wrapped workout bar to me. Her face reads overjoyed, with a dash of pity. I might puke just looking at it, holding it, thinking I’m absorbing its calories from my senses. What she doesn’t know is that I have a small spiral notebook hiding in my file cabinet, with chicken scratch as numbers representing the calories I eat for the day.

...

The remaining drops of coffee drip as a metronome into my mug. Coffee pools at the spout until the heaviness becomes too much and forms a droplet. Plop! The already settled coffee in the mug splatters just slightly, as if an ant were to make a cannonball into its very own ant-sized pool.

“Emily?”

I blink out the reverie I see in the coffee. “Mmh, yes?”

“Can you pick up the pizza tonight for dinner?”

“Sure can.” I turn toward my mom as she is picking up her work bag to leave.

“Holy shit, Emily...have you been sleeping?”

Unaware of my appearance, my eyebrows scrunch together to question her.

“Your undereyes are purple and bluish.” Her eyes scan my body head to toe. “And you’re so pale. I’ve never seen you this pale before.”

I turn back to the coffee, dismissing her continued stare. Grabbing the low fat milk to prepare my coffee, I feel her eyes burning my back with unasked questions.

“And why do your clothes look so...baggy?”

“Mom, I gotta go. I can’t be late for work,” I say, shoving the milk back into the refrigerator.

Her eyes continue to etch my every movement, figuring out the sudoku of my health problems.

“You’re going for your weekly check up today, right?”

“Yes, mom, as always.”

“We’ll talk over dinner then. I want an--” I slammed the garage door, ending her sentence prematurely.

...

I’m on the precipice of understanding what love is. I’m entering forbidden territory. I’m no longer the executioner of my soma. I’m an admirer. I see myself from the outside, like a ball of energy shoved somewhere deep - that thing; that soul of mine -- whisked itself out to look at myself. Sure, I have a few bruises, purple and green like an overly ripe fruit. Yet, if you continue to look, you will see the protruding bones. The angles are beautiful. I’m a precious doll, left on the shell. Who wouldn’t love someone, something so fragile? I just need to be handled with care. I’m finally handling myself with expert care.

How long do I have to wait?

“Excuse me, ma’am. I’ve been here for 25 minutes. I have a recurring appointment

with my doctor. Is something wrong?”

“Uh, let me check our notes. I just clocked in. What’s your name?”

“Emily Loveless.”

Her dark finger scans a binder of typed schedules on a spreadsheet. She comes to my name, I assume. “Yes, you’re still on. I’ll call you when you’re ready!” Her black curls bounce in unison with the lilt of fake positivity in her voice.

Back toward the seafoam waiting room chairs I anticipate the squeak my ass will make sitting on the plasticy outer veneer. The off-white walls display large pictures denoting so-called powerful words in the English language, like “integrity,” with a bird flying so close, but not touching some body of water beneath it. I never understood the meaning of those paintings -- the ones that are found in most office buildings, as if it is not a proper office building without one. They always left me a bit melancholy and less inspired.

A girl, no older than eight, with pigtails tied high in her hair, stares at me from across the room. I look away, only to momentarily return my glance toward her. Piercing gray-blue eyes stay locked on me. A worn doll, one a mom would make for their children in the ‘90s, is

nestled in her arms.

“It’s rude to stare, honey,” a woman who appears to be her mom says to her daughter, whose eyes only veer away when caught. When I peer back, I see her looking at me in short intervals so as not to make her mom suspect a thing. She shifts her small hand up to her mother’s ear and whispers not so quietly, “I’m scared for her, Mommy.”

“Emily Loveless,” the nurse I previously spoke with calls out.

“Another three pounds, Emily.”

I can’t make eye contact with the nurse taking note of my weight. Out of shame, my head faces the digital numbers on the scale. I lie.“I swear I don’t know how. I’m doing everything the doctor says.”

“Well, this isn’t between me and you. It’s between you and your doctor,” she says, leading me to a room for my weekly check-in. “Just a few minutes and the doctor will be in.” And the door is shut. I’m alone with the sterile smell keeping me company.

Scanning the clothing I’m wearing, I make sure the solid green shirt and boot cut jeans I have on are baggy enough to not show my body’s contours. I pull out my phone, and turn on the camera app to see my face. Skinny, slightly tired looking, but awake enough. I give it a heavy-handed slap. Pinch my cheeks for more color. Well-looking enough. I double check this every time I step into this room, taking account of what I look like, what changes they might see other than my decreased weight. My dangling legs begin to kick out of nervous anticipation. Sometimes the doctor takes a few minutes or a --

She walks in. My brows furrow.

“What are you doing here?”

“Honey, your doctor asked me to come in--”

“Is this some sick joke? What are you doing here?”

“We need to talk. I know what’s going on.”

“You don’t know anything...is this even legal?”

Now my mom’s brows furrow. For me it’s rage; for her concern. I want to slap the emotion off her face. She reaches her left arm out, placing her palm on my forearm closest to her, giving me a gentle touch. I shift my body, dodging what may next be a hug. Calming? Is this supposed to be calming?

“Get out now. I want my doctor.”

“Honey, you’ve been drastically losing weight. I’ve been waiting for you to tell me, but you haven’t...plus, I’ve heard. The staff talks.”

“Who told you? Does HIPPA mean crap to you and everyone else? What does privacy even mean to any of you?”

“They, like me, are just trying to look out for you. That’s all this is.”

“SHUT UP. SHUT UP. SHUT UP. This can’t be happening!”

Anger boils in my stomach. It starts to rise up into my chest, until my throat is burning. It comes out as a guttural scream. My mom’s eyes shift from side to side, knowing others must have heard it.

“GET OUT. GET OUT. GET OUT.”

“Honey, please stop,” she pleads.

Staff is knocking at the door, asking in tight, constrained voices if we need help. The voice is familiar. It’s one of the nurses I know.”

“It’s okay; we’re okay.”

‘HELP ME, DAMNIT.” My voice box is hot and sore from the shrieks.

“We will open the door. We have to, Susan. She’s our patient,” the nurse says opposite the closed door. As it creaks open, I jump down from the patient’s table, running out the door. Behind me I hear the nurse calling for security.

My mind grows dizzy, my body disoriented. Two large, uniformed men, fumble toward me. I can’t make out the features of their faces. They could be anyone.

“NOOOO. I’m fine. I’m FINE,” I scream at them, making a U-turn in the opposite direction, as one grabs my arms. I’m caught. Their grip seizes most of me, except for my flailing legs and my head. “STOOOP. I’m FINE. Stop hurting me.”

I see a blotch of red on one of their faces. The man appears to be covering it. “Why ME? Why? Stop hurting ME!”

A needle enters the surface of my soma. Not my soma.

Black consumes me.

Looking down at myself I see it. Everyone outside the hospital, those once preoccupied by their phones or in groups surrounded by small talk, stare in my direction now. They see an everyday girl’s body laying on a gurney, laced in a straitjacket.

It’s just another sad sight to see.

Jessica Clifford is a short story writer, poet, and former journalist. She views humans as Homo Narrans - the storytelling species - that understand each other only through shared experience (real or make-believe). She is published in The Coraddi literary magazine and two academic journals, including Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research and Carolinas Communication Annual.

‘Squirrel's Nest’

R. P. Singletary is a lifelong writer across genres of fiction, poetry, and hybrid forms; a budding playwright; and a native of the rural southeastern United States, with recent fiction, poetry, and drama appearing in Literally Stories, Litro, BULL, Cream Scene Carnival, Cowboy Jamboree, Rathalla Review, The Rumen, Bending Genres, D.U.M.B.O. Press, and elsewhere. Website: https://newplayexchange.org/users/78683/r-p-singletary

Christine Simpson is a working artist. She taught in the departments of Design Communications and Fine Art at the South East University, Waterford, Ireland, for many years. Christine is represented by So Fine Art, Dublin. Her work has been exhibited around the world and generally addresses subjects connected to our natural world, in particular the topic of climate change. Christine has received numerous awards. Her work has also been featured in many publications. Christine’s work is in many private collections and she regularly undertakes commissions for art pieces and commercial photographic illustrations.

Squirrel's Nest

Where do they go? It could've been mistletoe, what with all the leaves gone from the hardwood trees lining both sides of 11th Street. Captivated by the height of its airy mass, I almost stumbled in the recent rain's regurgitation of autumnal downward release, leaf afoot. No, not the holiday hopeful's wish high up there, though lovely the thought. Too much leafiness and tied together by twigs, this mess someone's comfort of home? The squirrels, the squirrels.

Holidays long troubled me. For years, general malaise would set in and I hadn't the maturity to understand. Around September, I'd come to notice in recent years, that's when not me alone would start grabbin' a jacket or sweater and take on a prickly air not right, unsettled, ill at ease, hungry. Hallowe'en munchies, yes. Turn of season more, always bad on the very young and very old, long been said across this section of New World. True all that, by some ancient standard. The older I grew, I felt something more, of expectation gone, grown greedy and lost in

its meaning, like leaf for house above, confusing me the disorder of nature's rule and border, labels.

As soon as earlier, earlier-posted, every year sooner, the back-to-school sales would sweep clean the shelves, store clerks following far-off Corporate's always-near mandate to trot out sooner, faster, more if not convincingly better Halloween, then more Thanksgiving, coming headlong into of course more Christmas and better New Year's ... and should I even continue to fill in the blanks with all the rest, festivities and honors, days created to conjure up, conspire toward more dollars devoted to meddlesome and endless purchasing, at what cost? Everything

deemed essential, all the must-haves necessary but unfulfilling; it won't settle down 'til Valentine's, Passover, Easter, or ... you see my point? At any rate, barely a partial summer to recuperate, and they keep addin' more, new colours needed for the 4th and on and on. I shall stop.

My mind deep, no longer stumbling in downed leaves yet to be gathered and cleared, the solitude of the unpeopled, otherwise-barren street caressed me, its chafing wind now dry and cracking reminding me of time, season, another place unlimited. I looked back up at the little nest of a house high in the sycamore tree (if with my phone, I'd have double-checked the species of trunk, hard to decipher only by wet mash of partial leaves beneath boots and clinging like a bad memory better washed). I waited and looked, not knowing for what, but delaying my routine turn of corner onto Main and back to life and the day's commerce. I'd commenced too early a wintry walk in this town so far south in the Lower 48. Southerners do not readily venture out in such weather, gaaa-rrrraaaashhhhh-cious!, I could hear them scream in street-length syllables, temps dipping below 60, oh my. And with Fahrenheit so far down ha the stick, the recent 'cold' snap moved, dropped, homeless from their customary corners. I hoped not into their graves, no joke.

Noise of any season. I knew the chatter flitting about my head. It was a squirrel's home, indeed, atop that tree. One lone creature. I didn't have my phone, as I said, or I would've searched on how long the newly birthed stay in such a nest – last spring so far away, surely the newbies, them youngins, gone by now, right? – and also posed of the web, older ones keep same bed from year to year?, squirrels mate for life?, and more. I left the minimammal alone. As if. That child's busy, real winter comin', did the guy or gal even know of me, audience of one and not payin'?

I focused on my new street. I had moved on Christmas Eve, back to the first apartment I'd leased in the town, really a small city by most measures. So many years ago then, the new building constructed and shiny, just opened when I drove around looking for a place to live way back when. neighborhoods evolve, unclear boundaries, ever-shifting colours and sights and sounds of people, their ways. So many changes since those years, mostly good, not much all that bad, I reasoned. I passed by a closed restaurant. Clearly, they'd made enough last night, New Year's, and all the remnants of expensive wining and dining scattered from front door to alley dumpster I could partly see in the morning light, shards of bottles, dozens of corks, gold and silver streamers, two red balloons tied to the street sign, the rest having popped, now shriveled and looking sad in the dim landscape. Don't wanna say goodbye either, I mumbled.

I saw my reflection in the establishment's front bay window, despite it being full of smudges and caked with grime. I glared at myself and laughed somehow. At least sunny, I could see parting borders within boundless sky, clouds behind me, a good day ahead, chilly, not cold, both my Yank neighbor and their new internet-love of the hour, half-day, or partial week corrected me last night. She had introduced me to their friend. It was awkward, but not new. For all three of us. As her barechested, boxered husband held open their door in the dark. He did wave with a half-smile, and in hindsight I contemplated that a missed invite. Gift? Turned down?

For me, it felt good to be back where I'd started, empty my nest-bed but unlimited in ways, my own love of the bounded years of marital minutes gone from my life and freeing perhaps from perimeter of prior century, petty the definitions' long hold. Gone, gone with the old year, gone that unique voice and frontier body and comforting, contorting hand of connection, the lines in two palms. Hers gone, forever from this life, hers and mine. No kids, at least that part made easier, but my mind hurried already, I sped up and worried; I didn't know what holiday it would take to dance across my calendar, what year to shimmy, for me to shake it all off and move on, more than a change of address needed to bury finally that relationship, if but been such by my own recollection of definition. Sure, yeah, it but been and a whole lot more. Yeah sure. Yeah.

Squirrelly, I left the urban quietude in greater wonder and scampered back into my apartment-home needing a cuddly blanket or unstiffed drink for warmth, but asking myself, what else might provide heat of heart for me, sensing more lack and lax in all the upcoming, ceaseless slew of seasons salient, every holiday alone at least for now with both parents, times two four siblings, deceased? I wasn't certain if I'd venture back out the rest of the day, maybe not the week's remainder, but this year would be different. If I gave it a rest to start. I could feel the change afoot, albeit tiny tiptoeing of movement within my heart's environs. Bothers of brittle leaves more fallen outside and in, brothers and sisters clearing the view of nature's magic for good, I considered we all make do and can move on in time, adjusting our borders to suit circumstances, those far beyond our little aged control. I reconsidered spring, my allergies, do squirrels suffer too, I wondered, they always seemed so busy.

R. P. Singletary is a lifelong writer across genres of fiction, poetry, and hybrid forms; a budding playwright; and a native of the rural southeastern United States, with recent fiction, poetry, and drama appearing in Literally Stories, Litro, BULL, Cream Scene Carnival, Cowboy Jamboree, Rathalla Review, The Rumen, Bending Genres, D.U.M.B.O. Press, and elsewhere. Website: https://newplayexchange.org/users/78683/r-p-singletary